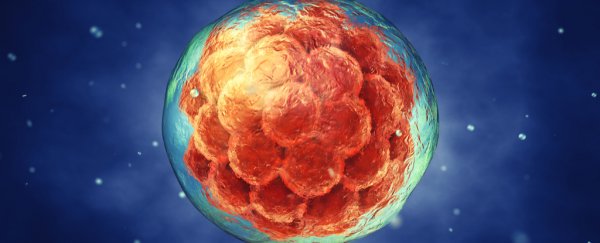

Scientists have successfully edited the DNA of human embryos to erase a heritable heart condition, cracking open the doors to a controversial new era in medicine.

This is the first time gene editing on human embryos has been conducted in the United States. Researchers said in interviews this week that they consider their work very basic.

The embryos were allowed to grow for only a few days and there was never any intention to implant them to create a pregnancy.

But they also acknowledged that they will continue to move forward with the science with the ultimate goal of being able to "correct" disease-causing genes in embryos that will develop into babies.

News of the remarkable experiment began to circulate last week, but details became public Wednesday with a paper in the journal Nature.

The experiment is the latest example of how the laboratory tool known as CRISPR (or Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats), a type of "molecular scissors," is pushing the boundaries of our ability to manipulate life and has been received with both excitement and horror.

The most recent work is particularly sensitive because it involves changes to the germ line, that is, genes that could be passed on to future generations.

The US forbids the use of federal funds for embryo research and the Food and Drug Administration is prohibited from considering any clinical trials involving genetic modifications that can be inherited.

A report from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine in February urged caution in applying CRISPR to human germ line editing, but laid out conditions by which research should continue. The new study abides by those recommendations.

Shoukhrat Mitalipov, one of the lead authors of the paper and a researcher at Oregon Health & Science University, said he is conscious of the need for a larger ethical and legal discussion about genetic modification of humans but that his team's work is justified because it involves "correcting" genes rather than changing them.

"Really we didn't edit anything, neither did we modify anything. . . . Our program is toward correcting mutant genes," Mitalipov said.

Alta Charo, a bioethicist at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, who is co-chair of the National Academies committee looking at gene editing, said that concerns about the work that have been circulating in recent days are overblown.

"What this represents is a fascinating, important and rather impressive incremental step toward learning how to edit embryos safely and precisely," she said. However, "no matter what anybody says this is not the dawn of the era of the designer baby."

She said that characteristics such as intelligence are influenced by multiple genes, and researchers don't understand all the components of how this is inherited much less have the ability to redesign it.

The research involved eggs from 12 healthy female donors and sperm from a male volunteer who carries the MYBPC3 gene which causes hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM).

HCM is a disease of the heart muscles that can be terrifying because it can cause no symptoms and remain undetected until it causes sudden cardiac death. There's no way to prevent or cure it, and it impacts 1 in 500 people worldwide.

At around the time the sperm was injected into the eggs, researchers snipped out the gene that causes the disease.

The result was far more successful than the researchers expected: As the embryo's cells began to divide and multiply, a huge number appeared to be repairing themselves by using the normal, non-mutated copy of the gene from the females' genetic material.

In all, they saw that about 72 percent were corrected, a very high number. Researches also noticed that there didn't seem to be any "off-target" changes in the DNA, which has been a major safety concern of gene-editing research.

Mitalipov said he hoped the technique could one day be applied to a wide variety of genetic diseases - more than 10,000 known disorders can be traced back to a single gene - and that one of the team's next targets may be BRCA, which is associated with breast cancer.

The first published work involving human embryos, reported in 2015, was done in China and targeted a gene that leads to the blood disorder beta thalassemia. But those embryos were abnormal and nonviable, and there were far fewer than the number used in the US study.

Juan Carlos Izpisua Belmonte, a researcher at the Salk Institute who is also a co-author on the new study, explained that there are many advantages to treating an embryo rather than a child or adult.

When dealing with an embryo in its earliest stages, only a few cells are involved, while in a more mature human being there are trillions of cells in the body and potentially millions that must be corrected to eradicate traces of a disease.

Izpisua Belmonte said that even if the technology is perfected, it could only deal with a small subset of human diseases.

"I don't want to be negative with our own discoveries but it is important to inform the public of what this means," he said. "In my opinion the percentage of people that would benefit from this at the current way the world is is rather small."

For this to make a difference, the child would have to be born through in vitro fertilisation and the parents would have to know the child has the gene for a disease to get it changed. But the vast majority of children are conceived the natural way, and this correction technology would not work in utero.

Mitalipov said he hoped regulators would provide more guidance on what should or should not be allowed.

Otherwise, he said, "this technology will be shifted to unregulated areas, which shouldn't be happening."

2017 © The Washington Post

This article was originally published by The Washington Post.