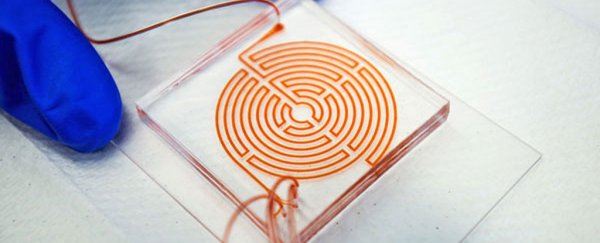

A new chip with a labyrinth design promises big improvements in detecting rare and aggressive cancer cells in the blood, helping doctors to anticipate tumour growth and plan customised treatments for their patients.

By controlling the flow of the blood through this micro-maze, the chip is able to separate out larger types of cells, including cancer cells and cancer stem cells known to be particularly malignant and resistant to drugs.

Such cancer cells can be one in a billion in a flow of normal white blood cells, and the new method is more effective and faster than current techniques at finding its targets, according to the team from the University of Michigan.

"You cannot put a box around these cells," says lead researcher Sunitha Nagrath. "The markers for them are so complex, there is no one marker we could target for all these stages."

Credit: Joseph Xu, Michigan Engineering Communications & Marketing

Credit: Joseph Xu, Michigan Engineering Communications & Marketing

These cancer cells occasionally get dislodged from cancerous tumours in the body, floating freely in the bloodstream, and they can reveal clues about the original growth – if they can be caught.

The cells are also thought to sometimes transform into cancer stem cells (CSCs), types of cells that can grow and feed new tumours, which is another reason scientists are keen to keep a close eye on them.

It's because the CSCs are so fluid and changeable that catching them is difficult with normal methods, which typically look for tell-tale proteins on a cell surface.

What the labyrinth design does is push larger (cancer) cells forward through the curves while smaller (regular) cells get stuck to the walls.

Also crucial are the many corners the researchers have built into their maze: It creates a flow that puts the smaller white blood cells in the perfect position to get snagged.

What's left at the other end is a much cleaner stream of cancer cells that scientists can then use for their analysis.

The new process is fast too, and by adding a second chip, the team was able to reduce the number of white blood cells in a sample by 10 in just five minutes.

Chalk it up as another success for microfluidics, an emerging field of science and technology where fluids are processed through very tiny channels to do anything from study the nanoparticles in blood to grow human tissue in a lab.

In this case, once the cancer cells are caught and filtered out, scientists can study them to find ones on their way to and from stem-like states. Testing was carried out using samples from patients with pancreatic and late-stage breast cancer.

The new technique is also being used in a breast cancer clinical trial, investigating the effectiveness of a treatment that blocks an immune-signalling molecule called interleukin 6 – experts think interleukin 6 enables cancer stem cells, and this labyrinth-on-a-chip should help to prove it.

"We think that this may be a way to monitor patients in clinical trials," says one of the team, Max Wicha. "Rather than just counting the cells, by capturing them, we can perform molecular analysis so know what we can target with treatments."

The research has been published in Cell.