Scientists have identified what they believe to be the missing brain connections that cause hallucinations for people with Parkinson's, a discovery which may help doctors predict and track the development of the disease in the future.

The new research, based on a series of functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) scans, points to brain areas associated with attention and visual processing as being at the root cause of these hallucinations.

With further follow-up studies, we might be able to tell who is at greater risk from hallucinations and eventually find ways to manage the problem, according to the team from VU University Medical Centre in the Netherlands.

"Visual hallucinations in Parkinson's disease are frequent and debilitating," says one of the team, Dagmar H. Hepp. "Our aim was to study the mechanism underlying visual hallucinations in Parkinson's disease, as these symptoms are currently poorly understood."

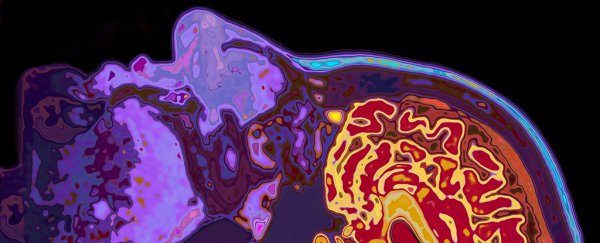

Reduced brain activity was noticed in those having hallucinations (bottom row). Credit: Radiological Society of North America

Reduced brain activity was noticed in those having hallucinations (bottom row). Credit: Radiological Society of North America

There's been little past research into hallucinations and Parkinson's disease using fMRI, and the few studies that have been carried out involved participants perfroming specific tasks. Here, the researchers wanted to look at subjects as they rested and did nothing.

That's because visual hallucinations have been strongly linked to cognitive decline in Parkinson's patients, so the researchers wanted to run scans where any kind of task or cognitive thought wasn't involved.

The study looked at 15 Parkinson's patients with visual hallucinations, 40 patients without hallucinations, and 15 healthy control subjects, looking at the synchronisation between activation patterns in different areas of the brain.

All the patients with Parkinson's disease showed less communication activity between brain regions, but in those with visual hallucinations, researchers spotted additional areas cut off from the rest of the brain.

"We found that the areas in the brain involved in attention and visual processing were less connected to the rest of the brain," says one of the researchers, Menno M. Schoonheim. "This suggests that disconnection of these brain areas may contribute to the generation of visual hallucinations in patients with Parkinson's disease."

The additional areas that went dark were located in the frontal cortex, temporal cortex, rolandic operculum, occipital cortex, and striatum parts of the brain.

In a subsequent test weighing up cognitive performance, the Parkinson's patients with hallucinations performed worse than Parkinson's patients without hallucinations in areas including orientation, language, memory, and perception.

Around 75 percent of people with Parkinson's suffer from hallucinations at some point, making the disease even more difficult to live with. If we can understand more about what's going wrong in the brain when this happens, we might be better able to treat it.

One idea put forward by the researchers is that stimulating these dark brain areas somehow could lessen the chance of hallucinations, but we'll need more research to find out for sure.

"Our findings argue against the notion that a single specific functional brain region or network is the neural substrate of visual hallucinations in Parkinson's," write the researchers in their paper.

"Rather, [we] supply further evidence for a more global loss of network efficiency, which could drive disturbed attentional and visual processing and thereby lead to visual hallucinations in Parkinson's."

The research has been published in Radiology.