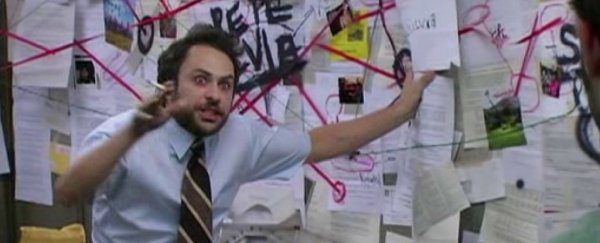

To a conspiracy theorist, the world is not what it seems. Invisible threads link seemingly unrelated concepts, and there's no such thing as a random coincidence.

Researchers have been scratching their heads for years over what makes some people more conspiratorially inclined. Now a recent study has finally tracked down one of the faulty thinking patterns. As it turns out, we all use it - but these people use it too much.

A team of psychologists from Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam in the Netherlands and the University of Kent in the UK has determined that conspiracy theorists are hooked on something called 'illusory pattern perception'.

"People often hold irrational beliefs, which we broadly define here as unfounded, unscientific, and illogical assumptions about the world," the team writes in the study.

"Although many irrational beliefs exist, belief in conspiracy theories and belief in the supernatural are particularly prevalent among ordinary, nonpathological citizens."

In other words, conspiracy theorists are not "nuts". They're totally sane, which makes their beliefs all the more puzzling - until we realise that they actually see the world quite differently.

Illusory pattern perception is a pretty simple concept. It happens whenever we find a meaningful pattern in random stimuli, drawing correlations and even causation where none has actually occurred.

For example, you might have a dream about an elderly relative, and then receive news the following day that the relative has passed away. For some people that would be enough to conclude that their dreams can predict the future.

We all do this with patterns to some extent, because that's how our brains work - and it's a useful tool for drawing conclusions about an environment full of cause, effect, and potential danger.

You may think illusory pattern perception is an obvious explanation for what's going on with conspiracy theorists. And it's true that researchers have assumed this phenomenon plays a role, but turns out they haven't actually been testing it.

"[I]t is surprising how little direct empirical evidence there is available to support the role of illusory pattern perception in irrational beliefs in general, and particularly in the domain of conspiracy theories," the team writes in the study.

To tackle this problem, the team devised a series of experiments. After recruiting 264 American adults, they started by assessing the participants' belief in both common and made-up conspiracy theories, on a scale of 1 to 9.

Amongst the conspiracies were things like " Ebola is a man-made virus," " the moon landing was a hoax," and the fictitious "the extract 'testiculus taurus' found in Red Bull has unknown side effects."

The researchers also ranked the participants' supernatural beliefs before moving on to a series of experiments designed to test whether people with high belief scores in conspiracies and supernatural stuff would also be more inclined to spot patterns in complete randomness.

After testing the subject's inclination for patterns on randomly generated coin tosses (conspiracy theorists found more patterns) the team moved on to pattern spotting in modernist artworks by Victor Vasarely (whose geometric works have obvious patterns) and Jackson Pollock (whose paint splatters are much more random, and any patterns spotted are more likely to be imaginary).

Curiously, conspiratorial and supernatural beliefs were only correlated with pattern spotting in Pollock's artwork, whereas people who spotted geometric patterns showed no specific inclinations towards any irrational beliefs.

Overall, this study has generated some pretty compelling evidence that our need to make sense of the world by generating patterns really goes into overdrive in those who veer towards conspiracy theories.

"We conclude that illusory pattern perception is a central cognitive ingredient of beliefs in conspiracy theories and supernatural phenomena," the team writes.

And that's super-useful to know. As infuriating as it may be to find yourself up late having an internet fight with a conspiracy theorist, remind yourself that they actually see the world differently, and might even be feeling lonely.

The research was published in the European Journal of Social Psychology.