When it comes to the future of space exploration, a number of new technologies are being investigated. Foremost among these are new forms of propulsion that will be able to balance fuel-efficiency with power.

Not only would engines that are capable of achieving a great deal of thrust using less fuel be cost-effective, they will be able to ferry astronauts to destinations like Mars and beyond in less time.

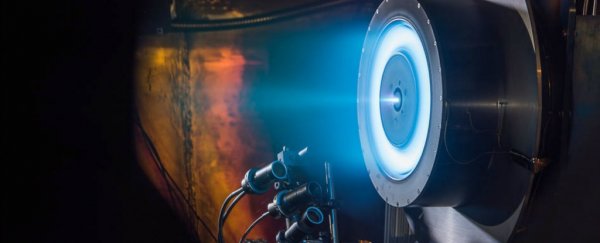

This is where engines like the X3 Hall-effect thruster comes into play. This thruster, which is being developed by NASA's Glenn Research Center in conjunction with the US Air Force and the University of Michigan, is a scaled-up model of the kinds of thrusters used by the Dawn spacecraft.

During a recent test, this thruster shattered the previous record for a Hall-effect thruster, achieving higher power and superior thrust.

Hall-effect thrusters have garnered favour with mission planners in recent years because of their extreme efficiency.

They function by turning small amounts of propellant (usually inert gases like xenon) into charged plasma with electrical fields, which is then accelerated very quickly using a magnetic field.

Compared to chemical rockets, they can achieve top speeds using a tiny fraction of their fuel.

However, a major challenge so far has been building a Hall-effect thruster that is capable of achieving high levels of thrust as well.

While fuel efficient, conventional ion engines typically produce only a fraction of the thrust produced by rockets that rely on solid-chemical propellants. Hence why NASA has been developing the scaled-up model X3 thruster in conjunction with its partners.

The development of the thruster has been overseen by Alec Gallimore, a professor of aerospace engineering and the Robert J. Vlasic Dean of Engineering at the University of Michigan.

As he indicated in a recent Michigan News press statement:

"Mars missions are just on the horizon, and we already know that Hall thrusters work well in space. They can be optimised either for carrying equipment with minimal energy and propellant over the course of a year or so, or for speed - carrying the crew to Mars much more quickly."

In recent tests, the X3 shattered the previous thrust record set by a Hall thruster, achieving 5.4 newtons of force compared with the old record of 3.3 newtons.

The X3 also more than doubled the operating current (250 amperes vs. 112 amperes) and ran at a slightly higher power than the previous record-holder (102 kilowatts vs. 98 kilowatts).

This was encouraging news, since it means that the engine can offer faster acceleration, which means shorter travel times.

The test was carried about by Scott Hall and Hani Kamhawi at the NASA Glenn Research Center in Cleveland. Whereas Hall is a doctoral student in aerospace engineering at U-M, Kamhawi is NASA Glenn research scientist who has been heavily involved in the development of the X3. In addition, Kamhawi is also Hall's NASA mentor, as part of the NASA Space Technology Research Fellowship (NSTRF).

This test was the culmination of more than five years of research which sought to improve upon current Hall-effect designs.

To conduct the test, the team relied on NASA Glenn's vacuum chamber, which is currently the only chamber in the US that can handle the X3 thruster.

This is due to the sheer amount of exhaust the thruster produces, which can result in ionised xenon drifting back into the plasma plume, thus skewing the test results.

NASA Glenn's setup is the only one with a vacuum pump powerful enough to create the conditions necessary to keep the exhaust clean. Hall and Kamhawi also had to build a custom thrust stand to support the X3's 227 kg (500 pound) frame and withstand the force it generates, since existing stands were not up to the task.

After securing a test window, the team spent four weeks prepping the stand, the thruster, and setting up all the necessary connections.

All the while, NASA researchers, engineers and technicians were on hand to provide support. After 20 hours of pumping to achieve a space-like vacuum inside the chamber, Hall and Kamhawi conducted a series of tests where the engine would be fired for 12-hours straight.

Over the course of 25 days, the team brought the X3 up to its record-breaking power, current and thrust levels.

Looking ahead, the team plans to conduct more tests in Gallimore's lab at U-M using an upgraded vacuum chamber. These upgrades will are schedules to be completed by January of 2018, and will enable the team to conduct future tests in-house.

This upgrade was made possible thanks to a US$1 million USD grant, contributed in part by the Air Force Office of Scientific Research, with additional support provided by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory and U-M.

The X3's power supplies are also being developed by Aerojet Rocketdyne, the Sacramento-based rocket and missile propulsion manufacturer that is also the lead on the propulsion system grant from NASA.

By Spring of 2018, the engine is expected to be integrated with these power systems; at which point, a series of 100-hour tests that will once again be conducted at the Glenn Research Center.

The X3 is one of three prototypes that NASA is investigating for future crewed missions to Mars, all of which are intended to reduce travel times and reduce the amount of fuel needed.

Beyond making such missions more cost-effective, the reduced transit times are also intended to reduce the amount of radiation astronauts will be exposed to as they travel between Earth and Mars.

The project is funded through NASA's Next Space Technologies for Exploration Partnership (Next-STEP), which supports not just propulsion systems but also habitat systems and in-space manufacturing.

This article was originally published with Universe Today. Read the original article.