Like so many others, 26-year-old Nia Payne wanted to view August's historic solar eclipse but didn't have a pair of protective glasses.

She walked outside on Staten Island and glanced at the Sun - 70 percent was covered - for about six seconds before deciding she needed eye protection.

She borrowed a pair of what looked like eclipse glasses from someone nearby, then looked directly at the Sun for 15 to 20 seconds.

They weren't the right glasses.

For two days after, Payne saw a black spot, shaped like a crescent similar to the eclipse itself, in the centre of her vision.

Finally, she went to the emergency room and was referred to the New York Eye and Ear Infirmary of Mount Sinai, where doctors performed a detailed scan of her retinas.

What they found astonished them and led to a study they published Thursday in JAMA Ophthalmology.

The black spot in her vision and the corresponding damage on her retina were mirror images of the eclipse itself.

It proved that scientists' "intuitions were correct" in their theories of how the Sun damages the eye, Avnish Deobhakta, assistant professor of ophthalmology at Mount Sinai and co-author of the study, told The Washington Post in a phone interview.

Doctors have long known of solar retinopathy, which is a "rare form of retinal injury that results from direct sungazing," the study noted.

It occurs when the Sun's energy essentially burns the retina. It can happen even when the Sun is obscured by the Moon during a solar eclipse, because many of the Sun's rays still reach the Earth.

The Mount Sinai doctors quickly diagnosed Payne with this injury, which was much worse in her left eye.

They asked her to draw the black spot she saw on a piece of paper. It was a crescent that looked a lot like the eclipse itself.

The doctors decided to take a closer look.

(JAMA Ophthalmology/New York Eye and Ear Infirmary of Mount Sinai)

(JAMA Ophthalmology/New York Eye and Ear Infirmary of Mount Sinai)

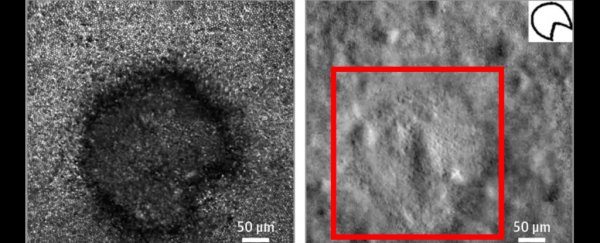

Mount Sinai has a precise imaging machine that uses adaptive optics, which can examine individual cells of the retina.

The machine only recently became an ophthalmology tool. According to Deobhakta, no previously published research showed what it found in patients whose eyes were damaged by a solar eclipse.

The researchers looked closely at the photoreceptor layer of the retina, which is the part that "takes in the Sun's light and converts it to electrical energy so our brains can make sense of light," Deobhakta said.

The Sun had burned a crescent onto her retina, just as in the image she drew.

"What we found is that the Sun's rays had damaged the photoreceptor layer in a very specific pattern, like a crescent," Deobhakta said.

"It really aligned with what she drew for us when we first saw her."

(Larry C. Lawson/CSM/AP)

(Larry C. Lawson/CSM/AP)

He said the finding is significant because it might be the first step to discovering a treatment for this sort of injury - which isn't all that uncommon.

While most people instinctively turn away from the Sun and solar eclipses are extremely rare, the kind of laser pointers that kids and pet owners often play with can cause similar injuries.

As of now, this sort of damage is irreversible, something Payne knows all too well.

She's currently training herself to mainly focus with her right eye. She has to sit close to the television to watch it, and reading remains a challenge.

The black crescent never disappears. And there's an embarrassment accompanying it.

"So far, it's a nightmare, and sometimes it makes me very sad when I close my eyes and see it," Payne told CNN.

"It's embarrassing. People will assume I was just one of those people who stared blankly at the Sun or didn't check the person with the glasses."

"It's something I have to live with for the rest of my life," she added.

This study might be the first step to ensuring she doesn't.

"There is no treatment on the horizon, but the horizon is only seen when you're able to see it, and I think that's what this imaging helps us to do," Deobhakta told CNN.

2017 © The Washington Post

This article was originally published by The Washington Post.