In the early years of the 20th century a Russian scientist – now known as the father of astronautics and rocketry – wrote a fable exploring what life in space might be like in the future.

Konstantin Tsiolkovsky (1857-1935) suggested that, by 2017, war and conflict would be eliminated by a world government. He also proposed this as the year humanity would acquire the technology to travel beyond the Earth.

That's 60 years after this happened in reality. So now that 2017 has been and gone, just how accurate were his other predictions?

What makes Tsiolkovsky's story – later published in English in 1960 as Outside the Earth – so intriguing is that he assembled a fictional dream team of the finest scientific minds from the 16th to 20th centuries to build a rocket capable of reaching orbit.

The scientists included Galileo Galilei (1564-1642), Isaac Newton (1642-1727) and Tsiolkovsky himself (under the pseudonym of Ivanov).

Using the voice of these legends of science, Tsiolkovsky described not only the practical aspects, but also the sensations and emotions of living in space. It's an extraordinary feat of the imagination.

Let's look at how Tsiolkovsky's thought experiment shapes up against reality.

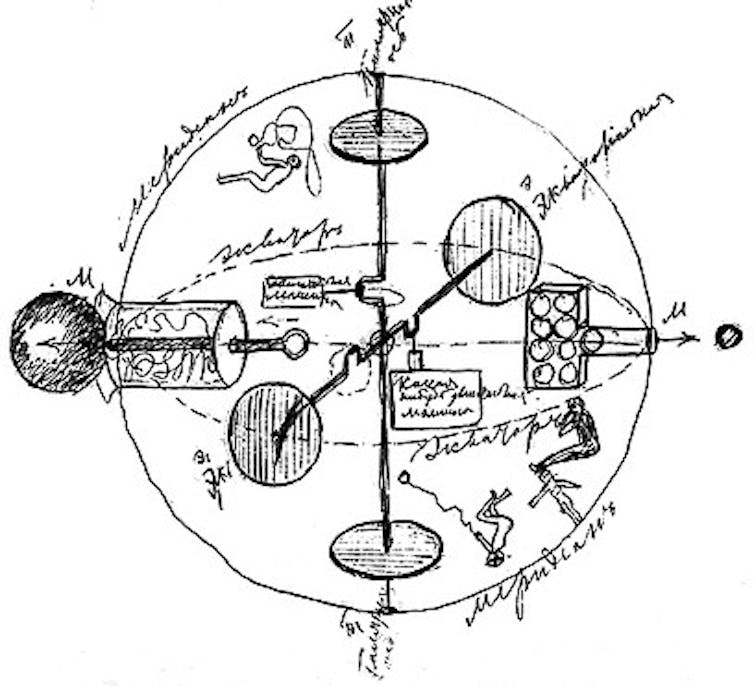

Tsiolkovsky idea for a spacecraft from 1883. (Wikimedia)

Tsiolkovsky idea for a spacecraft from 1883. (Wikimedia)

A rocket's eye view

Seen from orbit, space travellers are often struck by the beauty and fragility of the Earth and experience a cognitive shift of awareness. This is known as the Overview Effect and has been reported by astronauts and cosmonauts since the 1960s.

Tsiolkovsky anticipated this. In Outside the Earth, Newton warns the rocket crew that they may find the sight of the Earth overwhelming; and indeed there are mixed reactions:

The men were stunned by the sight, some felt exhausted and moved away from the portholes […] Others, however, darted excitedly from porthole to porthole with cries of surprise and delight.

What they don't experience, however, is another aspect of the Overview Effect: the realisation that national borders and terrestrial conflicts are ultimately meaningless.

Perhaps this is because our fictional cosmonauts are already living in a unified, peaceful world, something very far from where we are today.

In space, everyone is equal

Tsiolkovsky believed that the absence of gravity would erase social classes and promote equality.

In orbit, energy from the Sun is abundant and free. Little effort is needed to move heavy masses, so construction is cheap. Clothing is unnecessary because temperature can be easily regulated to a balmy 30 to 35 degrees Celsius. Beds and quilts are a thing of the past.

There's no longer any difference between the resources available to rich and poor – everyone can live in a fancy microgravity palace if they want.

As appealing as this vision is, in reality space travel is still the preserve of the very wealthy, whether individuals or nations. If anything, we risk differential access to space resources increasing, rather than eroding, inequality on Earth.

The orbital diaspora

Once our fictional explorers have successfully tested their rocket, they share the technology with anyone who wants to migrate to space.

Thousands of rockets are launched into geostationary orbit – the place where most of our telecommunications satellites are today, about 35,000 km above the Earth.

The colonists build orbital greenhouse habitats. Each is a cylinder 1,000×10 metres, housing 100 people. A soil-filled pipe runs through the centre, supporting a luxuriant ecosystem of fruit, vegetables and flowers.

Without seasons, weeds or pests, there's abundant food for our vegetarian colonists all year round.

In reality, people started living in orbit far earlier than Tsiolkovsky predicted. The first space station, Salyut 1, was launched in 1971.

The International Space Station has been permanently occupied in low Earth orbit for the past 17 years. But there's no orbiting ring of habitats where people can escape the hardships of life on Earth.

We now know that microgravity has serious effects on the human body, including loss of bone density and impaired vision. Living in space also means exposure to dangerous levels of radiation.

In any case, the cost of space travel is prohibitive for all but a tiny portion of the Earth's population.

Mining the solar system

Of course, resources are needed to maintain the orbital life described by Tsiolkovsky.

Newton and his rocket crew learn how to capture meteors and find that they contain an abundance of useful minerals: iron, nickel, silica, alumina, feldspar, various oxides, graphite and much more.

From these minerals, Newton says, building materials, oxygen for breathing, soil for plants and even water can be extracted.

While the orbital colonists are building their habitats, the rocket heads to the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter. A quick survey shows:

[… ] a rich and inexhaustible source of material for establishing colonies beyond the Earth's orbit.

Tsiolkovsky was right about the importance of off-Earth mining for future space economies. Here his prediction and real life are more aligned.

But while governments, private enterprises and researchers are pursuing the riches promised by the Moon and asteroids, there's a long way to go before the technology is equal to the task.

Leaving the cradle of Earth

A hundred years ago, Tsiolkovsky imagined that life in space would create an idyllic egalitarian society where people basked in orbiting greenhouses, drinking in the limitless energy of the Sun.

Instead, the wreckage of rockets and satellites orbits the Earth, splintering into ever smaller fragments that mirror the plastics proliferating in the oceans.

As space-for-profit competes with space as the common heritage of humanity, it's worth remembering that there are alternative visions of the future of human society, other worlds that we can aspire to.

In one thing we have far surpassed Tsiolkovsky's vision. At the conclusion of Outside the Earth, his cosmonaut-scientists talk of journeying from Mercury to the Rings of Saturn.

![]() Could he have imagined that, by 2018, the Voyager spacecraft would not only be travelling outside the Earth, but outside the Solar System?

Could he have imagined that, by 2018, the Voyager spacecraft would not only be travelling outside the Earth, but outside the Solar System?

Alice Gorman, Senior Lecturer in archaeology and space studies, Flinders University.

This article was originally published by The Conversation. Read the original article.