You've probably been on the edge of your seat wondering what the TRAPPIST-1 planetary system has been up to. Now we have four new studies that have probed the planets and its star, and found that they definitely bear further investigation in our search for extraterrestrial life.

According to four international teams, planets in the star's Goldilocks zone are rocky, like Earth; probably have water; and, based on Hubble observations, are more likely to have habitable atmospheres than we previously thought.

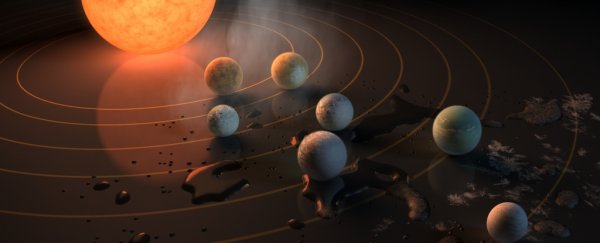

The discovery of the TRAPPIST-1 system, hailed as our "sister solar system", was announced a year ago, and for a while there, it was the discovery on everyone's lips: seven planets orbiting an ultra-cool dwarf star 39 light-years from Earth.

It looked like a pretty good candidate for finding extraterrestrial life.

Then it was discovered that maybe those planets aren't so hospitable after all. Then researchers discovered that, wait! They might be! It's been a real rollercoaster, and one that required further investigation.

Two of the new papers dropped in January. The first updated the planets radii, giving us more accurate physical measurements. The second updated and refined our understanding of the star at the centre of the system.

The other two papers, published this week, get into details about the planets themselves - analysing their atmospheres and the compositions.

Data from the Hubble Space Telescope helped perform a basic analysis of four of the planets' atmospheres. The research team was looking for an excess of hydrogen.

If there's too much hydrogen, there's no point looking further - hydrogen is a greenhouse gas that suffocates planets, and is unconducive to life as we know it.

The team looked to the planets' transits across the star. When a planet passes between us and a star, its atmosphere is backlit by the star behind it, as you can see in this incredible picture of Venus in front of the Sun. The differences in the light as it passes through the atmosphere can reveal details about its composition.

Just stop and think about that for a minute. We can find out what's in the atmospheres of planets nearly 40 light-years away.

The team's analysis found that at least three of the four planets studied had atmospheres that are not puffy and hydrogen-rich like gaseous Neptune's. This means it's worth taking a closer look with the James Webb Space Telescope - Hubble's successor - due to launch next year.

"Hubble is doing the preliminary reconnaissance work so that astronomers using Webb know where to start," said Nikole Lewis of the Space Telescope Science Institute, co-leader of the Hubble study.

"Eliminating one possible scenario for the makeup of these atmospheres allows the Webb telescope astronomers to plan their observation programs to look for other possible scenarios for the composition of these atmospheres."

The James Webb Space Telescope, which will be much more powerful than Hubble, will be able to probe deeper to find heavier gases such as carbon dioxide, methane, water, and oxygen. These will be able to narrow down the possibility that the planet is habitable.

Atmospheres don't really help life if the planet doesn't have a surface, though - and this is where the fourth paper comes in. Led by Simon Grimm of the University of Bern, an international research team has determined that all 7 planets are rocky, just like Earth.

But their densities also suggest that some of them have an incredible amount of water - up to 5 percent of their mass. Earth's mass, for context, is just 0.02 percent water.

It took almost a year for the team to work out the calculations for what Grimm called a "35-dimensional problem".

"The TRAPPIST-1 planets are so close together that they interfere with each other gravitationally, so the times when they pass in front of the star shift slightly," he said.

"These shifts depend on the planets' masses, their distances and other orbital parameters. With a computer model, we simulate the planets' orbits until the calculated transits agree with the observed values, and hence derive the planetary masses."

The form the water takes will probably depend on the planets' proximity to the star. Closer to the star means that the water is more like to be vapour, and farther means it's more likely to be ice, but some of the middle planets may have liquid water on the surface.

(NASA/JPL-Caltech)

(NASA/JPL-Caltech)

That's still no guarantee of life, though. The system is configured very differently from our own Solar System, with a small, cool star and the planets clustered relatively close. This proximity may mean that there's too much ultraviolet radiation from the star for life to form.

But whether or not there is life, TRAPPIST-1 remains a fascinating puzzle.

"No one ever would have expected to find a system like this," said Hannah Wakeford of STScI, who worked on the Hubble study. "They've all experienced the same stellar history because they orbit the same star. It's a goldmine for the characterisation of Earth-sized worlds."

The four studies (in order) can be found here, here, here and here.