Four years ago, a monster sunspot complex broke a solar record. As astronomers have just figured out, it was the source of the strongest magnetic field ever measured on the surface of the Sun.

It was, researchers at the National Astronomical Observatory of Japan concluded after five days of analysis, caused by gas outflow from one sunspot in the complex pushing against another sunspot.

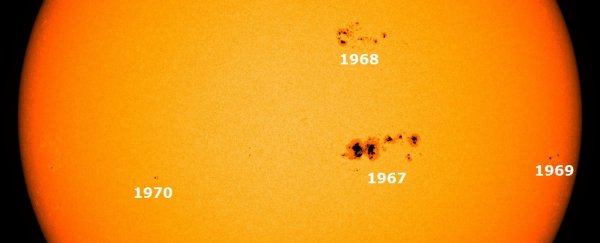

The sunspot complex, AR1967 (the AR stands for "active region"), appeared in February 2014, during which time astronomers around the globe took measurements.

At over 180,000 kilometres (111,847 miles) across, it was wider than Jupiter, and went on to morph into AR1990 and spit out an enormous X4.9-class solar flare on February 25.

But the magnetic field occurred earlier in the month; the team's data started from February 4.

Sunspots are called "active regions" for a reason. They look a bit like holes in the Sun, and are much darker and cooler than the rest of the visible surface, the layer of the Sun called the photosphere.

These regions are caused by magnetic fields, and usually occur in east-west pairs, with opposite polarities.

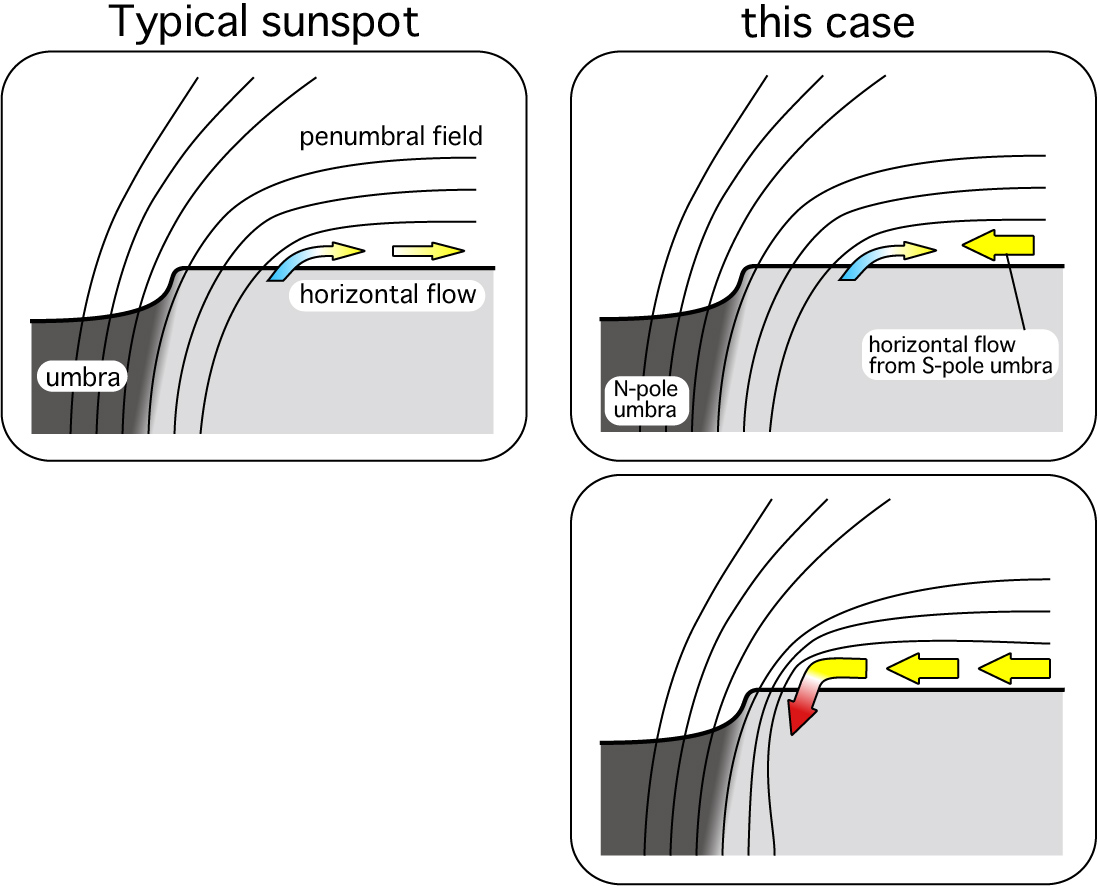

The magnetic fields are strongest in the darkest part of the sunspot, known as the umbra. Here, the magnetic field is around 1,000 times stronger than the surrounding photosphere and extends vertically.

In the lighter region, the penumbra, the magnetic field is weaker and extends horizontally.

Gas flows outward along the horizontal threads of the magnetic field in a sunspot's penumbra.

Joten Okamoto and Takashi Sakurai of the NAOJ were analysing data taken of AR1967 by the Solar Optical Telescope aboard the HINODE spacecraft when they found something really unusual - a signature for strongly magnetised iron atoms.

(NAOJ)

(NAOJ)

When they crunched the numbers, they found that the magnetic field had a strength of 6,250 gauss - more than twice the strength of the 3,000 gauss found in most other sunspots.

And it wasn't in the umbra, either, but the bright region between two sunspots of the complex.

Because HINODE observed the sunspot for a period of time, the researchers were able to check the data over the next few days. The strong magnetic field stayed in the bright region between the two umbrae.

They concluded that the strong field belonged to the southern spot's penumbra, the horizontal gas flows of which were compressing the northern spot's horizontal magnetic fields.

The research has been published in the Astrophysical Journal Letters.