It's 2018 and the common cold is still a thing. But if we're lucky, that might not be the case for much longer.

Scientists in the UK have developed a new molecule that prevents viruses responsible for the sickness from replicating inside human cells – and if further testing confirms the compound is safe, we could be looking at the unthinkable: a cure.

Of course, while we might call it the common cold, that oversimplified name doesn't really do justice to the more than 200 different virus strains forever vying to seize hold of your throat, chest, nose, and patience.

That viral variation is in fact is a big part of the reason why scientists have never succeeded in developing a single vaccine for the common cold – but a new approach led by researchers from Imperial College London could lay the foundations for a medication that actually treats the sickness, not just its symptoms.

Instead of going after these many and varied viruses – most of which are species of rhinovirus, of which there are some 160 recognised types – the new compound the team discovered, codenamed IMP–1088, focusses instead on something the viruses need: your cells.

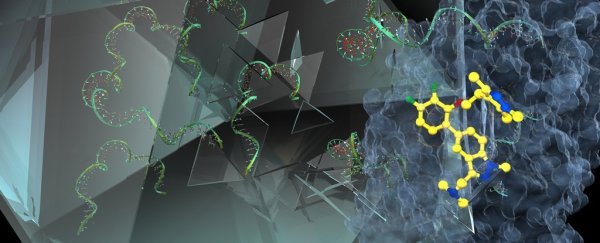

IMP–1088 (yellow) blocks human NMT (blue), preventing assembly of viral capsid (green) (Imperial College London)

IMP–1088 (yellow) blocks human NMT (blue), preventing assembly of viral capsid (green) (Imperial College London)

To replicate inside their host, viruses hijack a protein in human cells called N-myristoyltransferase (NMT), which they use to construct a capsid (shell) for protecting their genetic structure.

"Viruses hijack the host to make more copies of themselves," one of the team, cell biologist Roberto Solari explained to The Guardian.

"This enzyme is one of the host enzymes that the virus hijacks."

This hijacking behaviour isn't unique to rhinovirus. Other pathogens and parasites also drawn to the protein, including the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum.

In fact, it was while researching ways to inhibit P. falciparum from hijacking NMT that members of the team discovered the molecular structure of the new compound, IMP–1088, which inhibits viral binding to the protein with devastating effectiveness.

Scientists have investigated these kinds of NMT inhibitors before, but they've never previously struck upon this level of potency.

According to the team, IMP–1088 is up to 100,000 times more effective at blocking viruses from hijacking our cell proteins than previous efforts, which they say leads to "complete suppression" of viral replication and infectivity.

So far, these results have only been demonstrated in vitro – in experiments with human cells in the lab – so we don't have a proven cold cure that you can actually take.

But the good news is the research so far suggests IMP–1088 isn't toxic to our human cells – which cell inhibitors can sometimes be – meaning we've got a very promising candidate for potential human trials, which could begin in as little as two years.

For now, the researchers are cautioning that it's still very early days.

"We haven't done any animal studies, and we obviously haven't done any studies in humans, so I can't tell you formally what the animal toxicity of this compound is," Solari says.

"There is a still a long way before this becomes a medicine."

Be that as it may, the team is already investigating ways of making a version of IMP–1088 that could be inhaled – so that it gets into a patient's lungs as quickly as possible to block viral replication.

In addition, there's a chance the compound, if shown to be safe, could end up treating other conditions that also complicated by rhinovirus – such as asthma and cystic fibrosis.

Again, we'll have to wait to see the results of further tests before we know anything for sure, but for the millions or even billions of us who stand to catch a cold (or colds) this year, it's hard not to get a little excited about the amazing potential here.

The findings are reported in Nature Chemistry.