Picture a flea on Pluto's surface as seen through a telescope. This gives you some idea of the feat pulled off by astronomers, who managed to distinguish between spots of light on a 20-kilometre (about 12.5 mile) wide pulsar 6,500 light years away.

The result is mind-blowing on its own, but the physical processes behind the observation could help add much needed detail to one of the biggest mysteries in astronomy.

Canadian astronomers took advantage of a unique characteristic that magnified the spectrum of a pulsar's beams just enough to allow them to differentiate their positions.

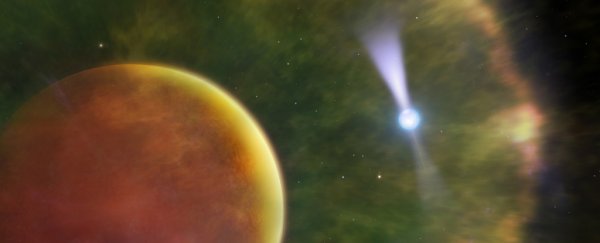

To understand this phenomenon, it helps knowing more about a far distant marriage made in hell. The pulsar PSR B1957+20 is a monster. Discovered thirty years ago, if it isn't the most massive object of its kind, it's up there with the record heavyweights.

A neutron star packed into a space no bigger than a large town, this beast spins several hundred times per second as it moves quickly around another, colder star in a roughly nine-hour orbit.

Like all pulsing stars of this nature, it flickers thanks to intense magnetic fields channelling electromagnetic radiation into two cones of incredibly intense radio waves.

If that's not metal enough for you, this beast of a star is slowly eating away at its companion.

For this reason PSR B1957+20 earned the nickname black widow – a pulsar now famous as the first in a class of neutron stars that chew away at a partner star with their radiation.

The distance between the pulsar and the larger brown dwarf is a few times that of Earth to the Moon – just close enough to allow an intense beam of pulsar radiation to bake its companion to temperatures matching those of our own Sun's heat.

The result is a cloud of plasma rising from the brown dwarf's surface into space, creating a diffuse shell of gas.

Much as starlight twinkles in our atmosphere, the light from the black widow pulsar distorts through changes in the plasma's densities as it orbits, offering astronomers the opportunity to get a closer look at its emission spectrum.

"The gas is acting like a magnifying glass right in front of the pulsar," says the study's lead author Robert Main from the University of Toronto.

"We are essentially looking at the pulsar through a naturally occurring magnifier which periodically allows us to see the two regions separately."

Demonstrating the feasibility of using a cloud of plasma to magnify light in this way is worthy of celebration on its own, but there was an added bonus to the discovery.

The structure of the frequencies in the pulsar's emissions looks a lot like those in something called FRB 121102 – an example of a microsecond blip of radiation known as a fast radio burst.

Fast radio bursts are typically seen just once, though FRB 121102 has become an interesting exception by putting on a repeat show. It's also polarised, lending further clues to its origin.

Still, tantalising hints aside, astronomers are yet to nail down the cause of this phenomenon.

While PSR B1957+20 isn't a known source of fast radio bursts, the fingerprints of this phenomenon in its spectrum is fuelling discussion.

"Many observed properties of FRBs could be explained if they are being amplified by plasma lenses," says Main.

"The properties of the amplified pulses we detected in our study show a remarkable similarity to the bursts from the repeating FRB, suggesting that the repeating FRB may be lensed by plasma in its host galaxy."

As usual, more evidence is needed before anybody can close the case on these mysterious bursts of radio waves.

Now that a method has been established for analysing the light from spinning neutron stars, we mightn't have to wait long our answers.

This research was published in Nature.