Psychopathy typically hovers on the border somewhere between a mental disorder and a moral judgement.

A new study on incarcerated volunteers adds vital detail to what is a complicated condition, suggesting those with psychopathic tendencies have impaired abilities to integrate sections of the brain that are essential for maintaining attention.

Nathaniel E. Anderson from the of The Nonprofit Mind Research Network and Lovelace Biomedical and Environmental Research Institute sees psychopathy as "wildly misunderstood".

"The public tends to view psychopaths as monsters and lost causes," Anderson told Eric W. Dolan at PsyPost.

Tests used to diagnose psychopathy tend to look for specific combinations of behavioural patterns, personality traits, and cognitive features.

To most of us, the term is relatively synonymous with a chronic lack of empathy, often resulting in manipulative behaviour that serves the individual. Put simply, psychopaths aren't regarded as nice people.

Importantly, the label isn't usually viewed as a mental illness grounded in biology, but rather as a morally corrupt personality trait – a fact that can make all the difference when applied in prosecuting a suspect.

Evidence has piled up over the years emphasising fundamental differences in the neurology of those who have a psychopathy diagnosis, such as variations in the prefrontal cortex.

To better understand the neurological underpinnings of the condition, Anderson and his team turned to research that suggested impaired attention played a role in psychopathic behaviours.

As compelling as such studies are, they suffer from several critical limitations.

One is they've relied largely on measuring changes in brain waves in response to a set of stimuli, which is a little like listening to the buzz of a crowd in gauging the response to a piece of news.

What Anderson wanted was a clearer understanding of the voices themselves, which means using tools that can zoom in on activity in different parts of the brain.

A second problem is most studies make use of individuals who have merely been identified with psychopathic traits according to a criteria list, such as the Hare Psychopathy Checklist.

This is a pretty straightforward process, but it doesn't necessarily imply these characteristics result in a pathology, making them fairly weak subjects to test.

Anderson's team put a call out for psychopathic volunteers who had landed in prison, and settled on 168 adult males at two medium-security state correctional facilities in New Mexico.

These inmates underwent something called an auditory oddball task, where they were required to listen to a sequence of sounds and click a button whenever they heard a specific high pitched tone.

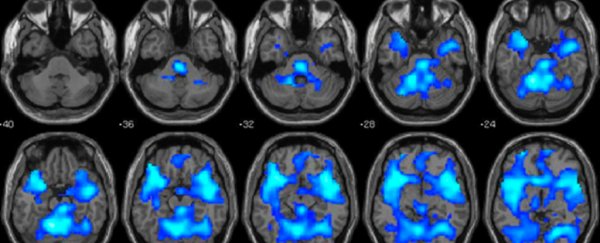

This was all conducted inside a functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) machine, which captured information on which parts of the brain were most active.

The end result backed up previous studies, confirming there were correlations between certain types of psychopathy checklist score and activity in certain brain pathways.

Regions involved in attention stood out, including zones in the 'decision making' prefrontal cortex and a part of the brain understood to play a role in memory called the anterior temporal cortex.

The study shows that while we might think psychopathy is all about empathy and emotion, there's a lot more to it.

"Specifically, the way the brain encodes differences between what is important and what is not, even without emotional content involved – and this has more to do with attention," says Anderson.

Since it focusses on a specific component of psychopathy, the study shouldn't be taken to be the final word on how it manifests.

The sample was also gender exclusive, which could mean we're missing a bigger picture.

Rather than excuse potentially criminal behaviour, studies like these could help reduce the risk of it developing in the first place by providing additional measures that reliably curb psychopathic tendencies.

Psychopathy needn't be a one-way ticket to evil. But if we're to reduce the potential harm caused by those who find it hard to pay attention to their emotions, we're going to need to know a whole lot more about it.

This research was published in Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience.