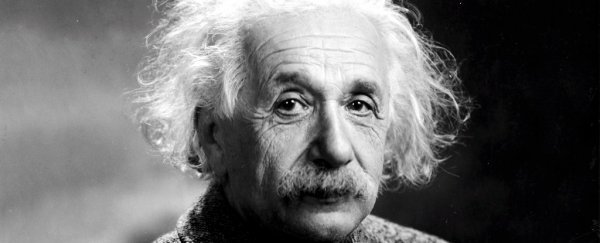

Not many of us can lay claim to being Nobel-Prize-winning theoretical physicists, but even if we're not Albert Einstein, we can still visualise ourselves in the great scientist's shoes.

If we can do that, surprising things might happen. A new study by scientists in Spain showed that when people assumed Einstein's physical identity as part of a virtual reality (VR) experiment, it actually changed the way they think – with some of the participants even improving their scores in cognitive tests.

"Virtual reality can create the illusion of a virtual body to substitute your own, which is called virtual embodiment," says computer scientist Mel Slater from the University of Barcelona.

"In an immersive virtual environment, participants can see this new body reflected in a mirror and it exactly matches their movements, helping to create a powerful illusion that the virtual body is their own."

That illusion is indeed powerful, Slater's new research shows, although the power conferred also has its limits.

In their virtual embodiment experiment, the researchers recruited 30 young men aged between 18 and 30, all of whom wore body-tracking suits and VR headsets for a virtual experience lasting approximately half an hour.

In the VR experience, half the group embodied an Albert Einstein avatar, while the other half acted as controls, experiencing the virtual environment in a generic male adult body.

Before their virtual trip, the participants performed a series of tests measuring different things, including: a test to detect any implicit bias against old people (much like the physically 'old' Einstein avatar), along with tests to measure self esteem, and also cognitive function.

"We wondered whether virtual embodiment could affect cognition," says Slater.

"If we gave someone a recognisable body that represents supreme intelligence, such as that of Albert Einstein, would they perform better on a cognitive task than people given a normal body?"

It seems like a strange hypothesis to investigate, but weird though it might be, the tests indicated just that – at least for one segment of the cohort.

Participants who exhibited low self esteem in the self esteem tests actually did better in a second round of cognitive tests after the VR experiment, but only if they'd embodied the Albert Einstein avatar during the virtual experience.

It's hard to know for sure why this might be, but the researchers speculate the immersive visualisation of themselves as the iconic physicist – a man regarded as a legend in terms of his intelligence and scientific achievements – resulted in a measurable boost in their test outcomes.

"Since Einstein can generally be considered a socially approved and highly accepted personality, one could argue that this leads to an improvement of self-esteem in low self-esteem people, which is it turn reflected in better cognitive performance," the authors write in their paper.

In a sense, it's possible that people with low self esteem have more to emotionally gain from this kind of embodiment experience, as people who are already feeling good about themselves going in to the VR session might be less emotionally affected by their role-play.

It's also worth pointing out that people who experienced the session as Albert Einstein also demonstrated reduced implicit bias against the elderly in a repeat of the bias tests after the VR experience – a reduction also not seen in the controls.

The researchers acknowledge further experiments with a wider group of both men and women is needed to see whether these intriguing findings can be replicated, but if they can be, it could lead to promising new directions in future research.

"It is possible that this technique might help people with low self-esteem to perform better in cognitive tasks," says Slater, "and it could be useful in education."

The findings are reported in Frontiers in Psychology.