After more than 125 years of mystery, scientists think they have reconfirmed the final resting place of the world's forgotten 'eighth wonder', clearing up much of the uncertainty from previous studies.

On 10 June 1886, Mt Tarawera blew its top in one of the largest volcanic eruptions in New Zealand's history, sending volcanic debris flying for as far as the eye can see and devastating the surrounding landscape.

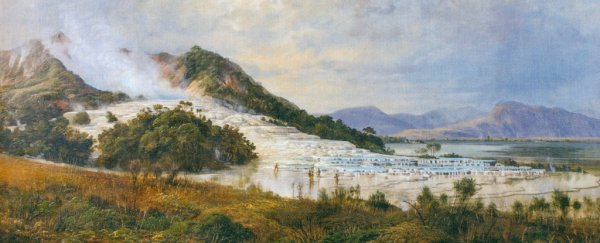

For hundreds of years, scientists assumed that the blast destroyed the eighth wonder of the world, New Zealand's stunning Pink and White Terraces, which were located on the shores of Lake Rotomahana just 10 kilometres south-west of the volcano.

More recently, there was speculation that perhaps they weren't lost after all, and had simply been buried beside the lake that rose up from the eruption - and potentially could even be investigated with an archaeological dig.

This new study uses detailed underwater mapping to confirm that while the White Terrace is long gone, at least part of the Pink Terrace remains in tact at the bottom of the massive Lake Rotomahana. But unfortunately it isn't something we'll likely be seeing again in our lifetimes.

Once upon a time, these pink and white terraces were Earth's two largest formations of silica sinter, a fine-grained version of quartz that dazzles in the sunlight. According to historical records, one of the formations was an exceptional pearly white, while the other had a tinge of pink colouring its many shelves.

Facing each other from across the lake, the unmatched geological structures would have been marvellous to behold, but three days after the historic eruption, both the lake and the Terraces had disappeared into a massive crater. Over time, the crater filled with water, replacing the lake that had once been lost.

Historic photographs, taken by the Burton Brothers in 1886, show the site before and after the massive eruption.

(GNS/University of Auckland)

(GNS/University of Auckland)

"The destruction of the majority of the Terraces is perhaps not surprising given that the 1886 eruption was so violent it was heard in Auckland and in the South Island," said lead author Cornel de Ronde, a research geologist at GNS Science in New Zealand.

"The blast left a 17km-long gash through Mount Tarawera and southwestwards beneath lake."

While experts believe the White Terraces have been largely destroyed, previous research has suggested the Pink Terraces are still hiding under the surface of the lake, which rose by at least 60 metres and increased in size by a factor of five following the historic eruption.

(GNS/University of Auckland)

(GNS/University of Auckland)

After reanalysing the overwhelming data collected five years ago, the researchers have provided an unparalleled glimpse beneath the lake's surface - and what they mapped matches up with historical photos of the Pink Terraces.

"We've re-examined all of our findings from several years ago and have concluded that it is untenable that the Terraces could be buried on land next to Lake Rotomahana," said de Ronde.

In other words, the Pink Terraces seem to have at least partially survived, but they're at the bottom of the lake - not buried under land.

Using historical photographs and maps in combination with modern technology - such as side-scan sonars, seismic surveys and magnetics - the researchers charted the lake floor with a degree of detail never seen before.

Importantly, their findings match Spencer's photographs and historical maps by pioneer geologist and explorer Ferdinand von Hochstetter, and show that at least part of the Pink Terraces are still there at the bottom of the lake, forgotten for all these years.

"Most people thought they had been destroyed, and why not?" said de Ronde in a video about the discovery posted in 2011.

"There was this huge and incredible eruption, which devastated the landscape…. So why wouldn't they destroyed? What is truly remarkable is that we have shown they haven't gone anywhere."

The findings may finally put to rest recent suggestions that there should be an archaeological site at the edge of the Lake to attempt to dig for the terraces. de Ronde called this idea "fruitless" in light of the reanalysis.

The study has been published in the Journal of The Royal Society of New Zealand.