While the presence of liquid water on Mars remains an ongoing topic of intense interest, we know that there is plenty of water ice adorning the Red Planet - and boy can it ever look amazing, as new images from the European Space Agency's Mars Express attest.

The Mars orbiter has obtained a stunning view of a feature called the Korolev crater, an 81.4-kilometre (50.6-mile) diameter crater just south of the Olympia Undae dunes circling the northern polar cap. The crater is filled almost to the brim with pristine ice year-round.

Like Earth, Mars does have seasons. And like Earth, the warmer seasons result in receding ice. But Korolev crater, created by a massive impact sometime in Mars's distant past, and named for Soviet rocket engineer Sergei Korolev, is a bit of an oddball.

It's a type of geological feature known as a 'cold trap', and that's exactly what it sounds like. The floor of the crater is very deep, just over 2 kilometres (1.2 miles) below the rim. From the floor of the crater rises a dome of water ice, 1.8 km (1.1 miles) thick and up to 60 km (37.3 miles) in diameter.

(ESA/DLR/FU Berlin, CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO)

(ESA/DLR/FU Berlin, CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO)

In volume, it contains around 2,200 cubic kilometres (528 cubic miles) of ice (although an unknown proportion of it is probably Mars dust).

When air travels over the ice (yes, Mars has air - it's unbreathable and thin, but it's there), it cools and sinks, resulting in a layer of cold air that sits directly above the ice. Since air is a poor conductor of heat, this cold layer acts as an insulator that protects the ice from warmer air, and therefore keeping it from melting.

The same dynamic is at play in the much smaller 36-kilometre (22.4-mile) Louth crater, also in the northern polar region of Mars.

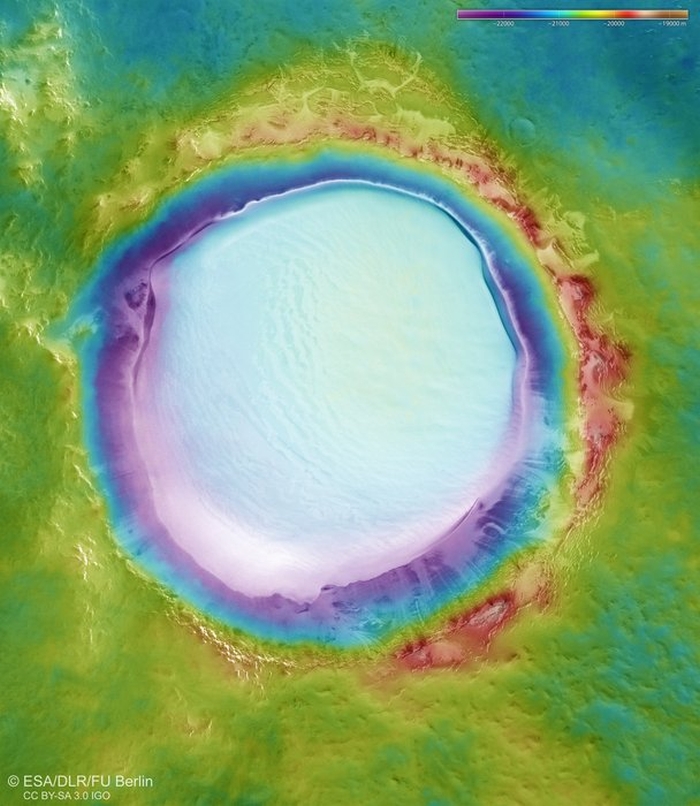

A topographic map of Korolev crater. (ESA/DLR/FU Berlin, CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO)

A topographic map of Korolev crater. (ESA/DLR/FU Berlin, CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO)

Mars Express - which celebrates its 15th anniversary in Martian orbit on December 25 - made several passes over Korolev crater last year, taking image strips with its DSLR High Resolution Stereo Camera (HRSC).

Five of these strips were stitched together to create the incredible collage you saw at the top of this article, showing the crater in its full glory, at a resolution of approximately 21 metres (69 feet) per pixel.

They were also used to create a colour-coded topographic map (above), which shows the elevations of the crater and surrounding plain.