Scientists have found mounting evidence that Parkinson's could start in the gut before spreading to the brain, with one study in 2017 observing lower rates of the disease in patients who had undergone a procedure called a truncal vagotomy.

The operation removes sections of the vagus nerve - which links the digestive tract with the brain - and over the course of a five-year study, patients who had this link completely removed were 40 percent less likely to develop Parkinson's than those who hadn't.

According to the team led by Bojing Liu from the Karolinska Instituet in Sweden, that's a significant difference, and it backs up earlier work linking the development of the brain disease to something happening inside our bellies.

If we can understand more about how this link operates, we might be better able to stop it.

"These results provide preliminary evidence that Parkinson's disease may start in the gut," said Liu.

"Other evidence for this hypothesis is that people with Parkinson's disease often have gastrointestinal problems such as constipation, that can start decades before they develop the disease."

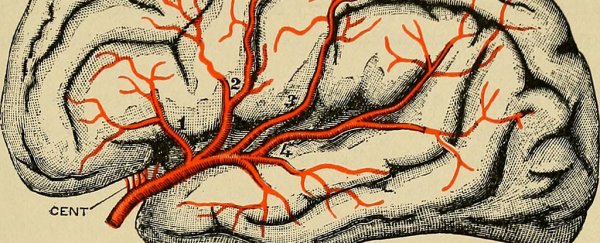

The vagus nerve helps control various unconscious processes like heart rate and digestion, and resecting parts of it in a vagotomy is usually done to remove an ulcer if the stomach is producing a dangerous level of acid.

For this study, the researchers looked at 40 years of data from Swedish national registers, to compare 9,430 people who had a vagotomy against 377,200 people from the general population who hadn't.

The likelihood of people in these two groups to develop Parkinson's was statistically similar at first - until the researchers looked at the type of vagotomy that had been carried out on the smaller group.

In total, 19 people (just 0.78 percent of the sample) developed Parkinson's more than five years after a truncal (complete) vagotomy, compared to 60 people (1.08 percent) who had a selective vagotomy.

Compare that to the 3,932 (1.15 percent) of people who had no surgery and developed Parkinson's after being monitored for at least five years, and it seems clear that the vagus nerve is playing some kind of role here.

So what's going on here? One hypothesis the scientists put forward is that gut proteins start folding in the wrong way, and that genetic 'mistake' gets carried up to the brain somehow, with the mistake being spread from cell to cell.

Parkinson's develops as neurons in the brain get killed off, leading to tremors, stiffness, and difficulty with movement - but scientists aren't sure how it's caused in the first place. The new study gives them a helpful tip about where to look.

The Swedish research isn't alone in its conclusions. In 2016, tests on mice showed links between certain mixes of gut bacteria and a greater likelihood of developing Parkinson's.

What's more, earlier in 2017 a study in the US identified differences between the gut bacteria of those with Parkinson's compared with those who didn't have the condition.

All of this is useful for scientists looking to prevent Parkinson's, because if we know where it starts, we can block off the source.

But we shouldn't get ahead of ourselves - as the researchers behind the new study point out, Parkinson's is complex condition, and they weren't able to include controls for all potential factors, including caffeine intake and smoking.

It's also worth noting that Parkinson's is classed as a syndrome: a collection of different but related symptoms that may have multiple causes.

"Much more research is needed to test this theory and to help us understand the role this may play in the development of Parkinson's," said Lui.

The research was published in Neurology.

A version of this story was first published in April 2017.