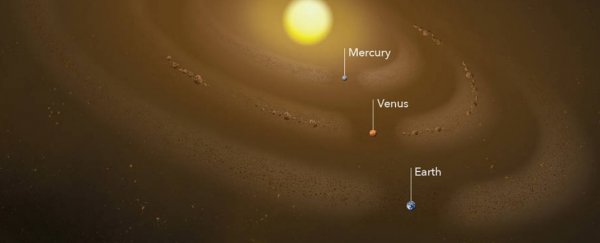

Our Solar System is filled with dust from crumbling asteroids and comets, but only some planets are honoured with a grainy ring to call their own. Both Venus and Earth have this pleasure, escorted around the Sun by a band of cosmic matter.

The little planet of Mercury, on the other hand, was once thought to be all alone. Pressed right up against the Solar System's only heat source, scientists didn't even dream that dust could survive here.

It turns out we were wrong.

A new study has now identified a vast trail of fine cosmic dust in Mercury's orbit, forming a ring nearly 15 million kilometres wide (9.3 million miles).

Unbeknownst to us, it appears that Mercury has been wading through this sea of ancient matter, three times bigger than itself, for likely billions of years.

"People thought that Mercury, unlike Earth or Venus, is too small and too close to the Sun to capture a dust ring," says co-author Guillermo Stenborg, a solar scientist at the Naval Research Laboratory.

"They expected that the solar wind and magnetic forces from the Sun would blow any excess dust at Mercury's orbit away."

In truth, Stenborg and his colleague Russell Howard, a solar scientist at the same lab, stumbled up their discovery by accident. The team was really looking for gaps in the dust, close to the Sun where the matter should have been vaporised and swept clean.

This is a bit like looking out a rain-splattered window and trying to figure out if it's still pouring outside.

With all the dust obscuring our immediate vision, scientists haven't been able to find any dust-free spaces between us and the Sun. From where we are sitting, it simply looks like there's dust everywhere.

The only clues we really have are the different types of light we see shining back at us. When sunlight bounces off of dust particles in space, it creates a force 100 times brighter than coronal light itself.

Most of the time, scientists throw this data away so they can focus solely on studying the corona, but this time, on a whim, the researchers kept it.

Using pictures of interplanetary space from NASA's STEREO satellite, the team built a model that separates both kinds of light, calculating how much dust there really is out there.

What they noticed was an enhanced brightness circling all the way around Mercury's orbit, implying "an excess dust density of about 3 percent to 5 percent at the centre of the ring."

"It wasn't an isolated thing," Howard explains. "All around the Sun, regardless of the spacecraft's position, we could see the same five percent increase in dust brightness, or density. That said something was there, and it's something that extends all around the Sun."

The results have pushed our understanding right to the brink. Because if Mercury really does wade through cosmic dust, then this material must be able to get far closer to the Sun than we ever thought possible.

This, in turn, gives scientists important clues about the composition and origin of the dust itself.

Researching dust rings in our Solar System is not all that different to reading tree rings in the forest. Composed of ancient rubble from 4.6 billion years ago, orbiting clouds of dust could help us explain what has happened since our Solar System first formed.

In fact, scientists think that all the planets in our system, including Earth, started off as mere grains of dust before they were pulled together by gravity and other forces.

"In order to model and accurately read the dust rings around other stars, we first have to understand the physics of the dust in our own backyard," says Kuchner.

The massive dust ring that co-orbits Venus is a good start. Just this month, a new paper claims to have figured out the true source of Venus's massive dust ring, which is made up of grains no bigger than coarse sandpaper.

Using dozens of different modelling tools and simulations, the researchers think the dust comes from a group of previously unseen asteroids co-orbiting with the planet.

What's more, the authors argue that this population of crumbling asteroids has been feeding Venus's dust ring ever since the Solar System's infancy.

"It's not every day you get to discover something new in the inner Solar System," says Marc Kuchner, an author on the Venus study and astrophysicist at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center.

"This is right in our neighbourhood."

The first and second study have both been published in the Astrophysical Journal Letters.