Hallucinations, delusions, thoughts of suicide and homicide. All the signs pointed to the 14-year-old patient having rapid onset schizophrenia. But when the usual treatments failed, physicians looked elsewhere and found a very different problem.

The true culprit for the teen's decline in mental health was a pathogen associated with what's known as 'cat scratch disease'. While the patient is now doing well, the case has left researchers curious about links between infection and neurological illness.

Bartonella henselae is a bacterium commonly carried in the blood of cats, especially kittens. Transmitted through a bite or scratch, it can produce localised swelling and lesions, and occasionally more serious problems in the heart and nervous system.

One thing B. henslelae isn't commonly known to cause is schizophrenia.

So when a happy, socially active male adolescent suddenly developed a range of psychiatric symptoms in 2015 – including threats of suicide amid claims to be the "damned son of the devil" – nobody initially thought to look for signs of an infection.

The teen's story might help change all of that. Researchers from North Carolina State University in the US suggest it could be a clear example of a link we've previously overlooked.

"This case is interesting for a number of reasons," says veterinary medical scientist Ed Breitschwerdt.

"Beyond suggesting that Bartonella infection itself could contribute to progressive neuropsychiatric disorders like schizophrenia, it raises the question of how often infection may be involved with psychiatric disorders generally."

The young patient's outcome was a happy one in the end, but it took some time to get there.

Initial treatments weren't altogether ineffective. A week on aripiprazole while in hospital helped reduce suicidal and homicidal ideation, but still left him experiencing psychosis.

Over the following weeks he became increasingly dysfunctional, full of outbursts of rage and irrational fears, making his normal life impossible. Somewhat ominously, he even suspected the family cat was out to kill him.

The medial team had a real mystery on their hands, after various treatments for the psychosis and other possible causes of the symptoms such as an auto-immune condition failed.

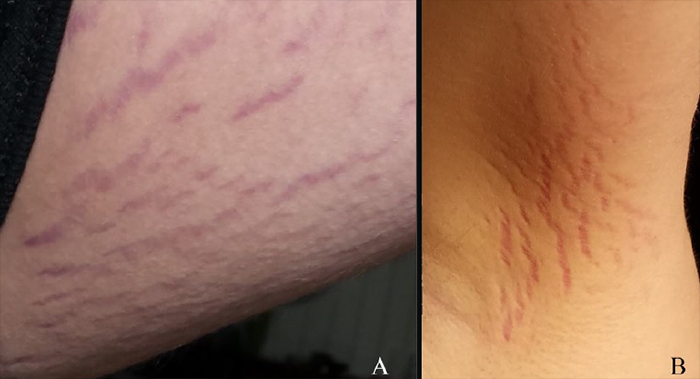

It wasn't until roughly ten months later that his parents first chanced upon the first clue that something else was going on. They were little more than red stripes across his skin – rashes commonly taken as the kinds of stretch marks teenagers get as they grow.

Cutaneous lesions on the patient's thigh (A) and ankle (B) (Breitschwerdt et al., JCNSD, 2019)

Cutaneous lesions on the patient's thigh (A) and ankle (B) (Breitschwerdt et al., JCNSD, 2019)

In early 2017 a physician evaluated the stretch-mark-like lesions and connected the dots, suggesting the cat-borne bacteria just might be behind the psychosis.

Blaming a pathogen isn't as left-field as it sounds. It's not unknown for neurobartonellosis – the neurological impact of a Bartonella infection – to influence behaviour, causing episodes of confusion and other neurological symptoms.

There's also mounting evidence suggesting the protozoan parasite Toxoplasma gondii, also associated with our tiny feline friends, is somehow linked to schizophrenia.

Thankfully, the kid's symptoms of psychosis faded after a course of antimicrobial chemotherapy, returning him to his previous state of physical and mental health.

That's good news for the teen and his family, but the case also gives researchers an intriguing piece of evidence supporting the emerging view that in at least a proportion of cases, symptoms of neurological impairment just might have its roots in an infection.

We're not just talking schizophrenia here, either. Everything from Alzheimer's to Parkinson's disease could have a complicated relationship with microbes. What we take as single diseases could represent a plethora of sub-types, with different causes and presentations.

"Beyond this one case, there's a lot of movement in trying to understand the potential role of viral and bacterial infections in these medically complex diseases. This case gives us proof that there can be a connection, and offers an opportunity for future investigations," says Breitschwerdt.

The interplay between our minds and our body's microbes – both those we need and unwanted invaders – is looking far more complex than we ever expected.

This research was published in the Journal of Central Nervous System Disease.