For as long as we've explored the oceans there have been tales of monsters lurking below. No doubt many sightings have been glimpses of actual marine life, but emerging sightings of long-necked serpentine beasts such as the Loch Ness Monster aren't as easy to explain.

Speculation on what could inspire changes in the old sea serpent have centred not only on the bodies of living animals but the bones of ancient ones. It's a nice idea, but until now it's been a little thin on the evidence. Finally we have the statistics to back it up.

Charles Paxton from the University of St Andrews and Darren Naish from the University of Southampton in the UK took an intriguing hypothesis on sea serpents that has been floating about for more than half a century and applied a heavy dose of scientific scrutiny.

In the late 1960s, American science fiction author Lyon Sprague de Camp suggested that a change in how sea serpents were described in 19th century reports of marine 'monsters' might have been caused by surging public interest in fossils.

"After Mesozoic reptiles became well-known, reports of sea serpents, which until then had tended towards the serpentine, began to describe the monster as more and more resembling a Mesozoic marine reptile like a plesiosaur or a mosasaur," De Camp wrote in a 1968 edition of The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction.

As far as possibilities go, it sounds plausible enough.

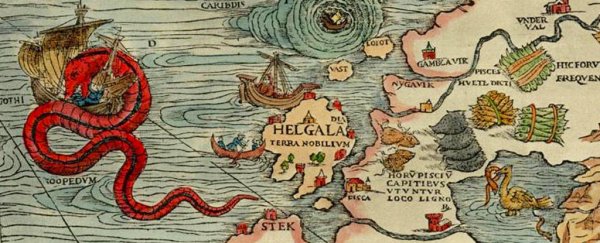

In centuries past, fearsome creatures of the ocean depths might have been more like Olaus Magnus's 90 metre-long (300 foot) 'sea orm' – huge, undulating serpents that curled around ships and dragged them to their doom.

Fast forward to more modern times, and sea monsters have come to resemble the classic 'Nessie' shape, with extended necks and hump-backs, driven by paddle-like appendages.

There were once, of course, reptiles of substantial size that resembled such animals. While dinosaurs walked the land, a rich variety of plesiosaurs swam in our planet's oceans.

By the mid-19th century, gentlemen geologists were not only discussing their collections of fossilised remains of such ancient reptiles among themselves, museums were putting them on display and bringing a history of long-lost 'monsters' to public attention.

It's not hard to imagine artistic license leaning heavily on iconic imagery as reporters turn an exciting splash or shadowy movement into something tangible. It makes more sense than a spontaneous appearance of massive animals that have been dead for 65 million years.

But even the most credible-sounding explanations still need supporting evidence.

Daniel Loxton knows this better than most. Co-author of the book Abominable Science and long-time cryptid skeptic, Loxton understands the challenges involved in making sense of a long history of reports of uncatalogued creatures known as 'cryptids'.

"There have been decades of attempts to compile and analyse databases of cryptid reports," Loxton told ScienceAlert.

"Those have always been problematic because eyewitness reports are not at all uniform. Researchers also introduce bias in curating their report collections to exclude reports they view as excessively implausible."

Loxton's own work helped inform this latest attempt to unravel the strange history of sea serpents. Rather than treating anecdotes of strange creatures as faithful depictions of an observed event, his approach has been to step back and treat them for what they are – reports.

"Paxton, Naish and I are all part of a trend toward cultural analysis of cryptozoological claims. A cultural approach seems to have much greater explanatory power and is at least as interesting a subject for exploration," says Loxton.

While Loxton's research has been strongly informed by a background in humanities, Paxton and Naish took a purely statistical approach in their investigation.

"It took a very long time reading books and magazine articles and other sources for accounts of monsters and then coding them into a spreadsheet," Paxton told ScienceAlert.

"It was fun at first and then it became tedious … but now I can do analysis!"

Their figures show that there was a decline in traditional reports of serpentine monsters as instances of long-necked plesiosaur-like animals increased, bolstering de Camp's speculation of a link between popular science and a fringe belief.

The result of that analysis isn't quite proof that a popularisation of Mesozoic reptiles was solely responsible for the sea monsters' evolving shape.

For one thing, long-necked reptiles weren't the only monsters making waves. Lizard-like marine reptiles called mosasaurs were also on display, yet seemed to influence surprisingly few sea monster sightings themselves.

But we at least have data that aligns the timeline of changes in awareness of extinct marine reptiles and iconic sea monster imagery.

The interplay between popular depictions and the public imagination is no doubt complex, and open to a variety of influences. But we shouldn't be so quick to dismiss those stories out of hand. There's gold in those narratives, if we treat them right.

"Anecdotes are often thought not to be amenable to scientific scrutiny," says Paxton.

"That is often the case but not always if they are handled carefully. With imagination there is a lot of good science we can do on topics which some people consider 'pseudoscientific'."

This research was published in Earth Sciences History.