From deep in the shale beds of Arctic Canada, what seems to be the earliest evidence of life on land has emerged. The discovery of microscopic fossils just pushed back the earliest recorded appearance of fungus by more than half a billion years.

This was the early Neoproterozoic Era, the last era in the Precambrian supereon, after multicellular life had exploded in the world's oceans, but before - we had thought, at least - it had arrived on dry land.

These newly analysed fossils - if the analysis holds up - date back to between 900 million and 1 billion years, which means they could take the crown of the first multicellular life on land (there's evidence of microbial terrestrial life that's significantly older).The previous oldest known and uncontested fungus fossils hail from a 407 million-year-old bed in Scotland.

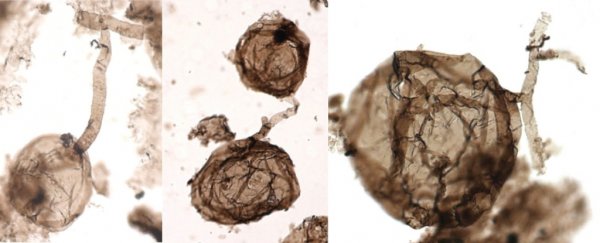

The newly discovered fungus, found in the Grassy Bay Formation, has been named Ourasphaira giraldae, and the fossils are surprisingly well preserved and intricate.

The researchers were able to make out multicellular, branching, septate filaments, with bulbous spheres on the ends, which make up the mycelium of a fungus.

They were also able to identify, using Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy, the presence of chitin - a compound found in the cell walls of fungi. Additionally, transmission electron microscopy revealed details of a bilayered cell wall structure.

"The combination of the microfossil morphology, wall ultrastructure and chemistry of these microfossils is consistent with a fungal affinity," the researchers wrote in their paper.

The appearance of fungus fossils more than half a billion years older than the oldest unambiguous specimen is certainly a surprise - but not actually as big a surprise as you might think. And it could solve another mystery that has been bothering scientists.

We know fungus was around when the first plants began to emerge around 500-600 million years ago, but the fungal molecular clock had already suggested these life forms should have been around sooner.

This clock is the mutation rate of biomolecules in DNA, which can be used to determine the evolutionary history of an organism. In the case of fungus, if it had emerged around the same time as plants, its molecular clock would reflect this.

Instead, the DNA of fungus indicated that it made its first appearance over a billion years ago. This discrepancy between the fossil record and the molecular clock has been a huge puzzle.

Add to this new analysis the fact that fungus fossils are often very difficult to identify, and we may be approaching an answer.

O. giraldae is certainly a fascinating find. It single-handedly resolves the discrepancy between the fossil record and the DNA record, while also pushing back the timeline for the Opisthokonta supergroup of organisms - encompassing animals, fungi and protists - to a billion years ago.

The researchers are confident.

"As multidisciplinary studies of Proterozoic fossil assemblages progress, we predict that more fossil fungi and other early eukaryotes will be discovered and will improve our understanding of the evolution of the early biosphere," they wrote.

The research has been published in Nature.