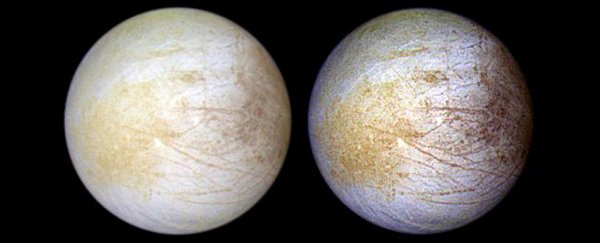

Thanks to the far-reaching optics of the Hubble telescope, and some smart visible-light spectral analysis, scientists have detected what looks a lot like sodium chloride - or good old table salt - on Jupiter's moon Europa.

That means the salty ocean hidden just beneath the surface of this moon could be more like Earth's oceans than we previously thought; it also challenges our current understanding of Europa's geological composition.

Previously, NASA probes Voyager and Galileo had already strongly suggested the presence of a salty liquid ocean under an icy surface shell on Europa, but it was thought that the salt in question was magnesium sulphate-based, like Epsom salts.

A switch in analysis techniques led to the new discovery. In this case, scientists used a spectrometer concentrating on the visible spectrum of light rather than the infrared spectrum, together with high-resolution images from Hubble.

"No one has taken visible-wavelength spectra of Europa before that had this sort of spatial and spectral resolution," says lead author of the new study, planetary scientist Samantha Trumbo from the California Institute of Technology (Caltech).

"The Galileo spacecraft didn't have a visible spectrometer. It just had a near-infrared spectrometer, and in the near-infrared, chlorides are featureless."

Higher quality imagery from the W. M. Keck Observatory had already hinted that sodium chloride might be present, but getting additional evidence across the vast reaches of space wasn't a straightforward process.

The researchers built on previous work from 2017, where sodium chloride put under Europa-like conditions in the lab exhibited chemical changes that would make it show up on a visible-light spectrometer.

Armed with this information, the team used the Space Telescope Imaging Spectrograph (STIS) on board Hubble, and was able to spot signs of irradiated table salt compounds in the visible spectrum at 450 nanometers; this matched the lab tests.

Europa conditions being simulated in the lab. (NASA/JPL-Caltech)

Europa conditions being simulated in the lab. (NASA/JPL-Caltech)

"Sodium chloride is a bit like invisible ink on Europa's surface," says astrobiologist Kevin Hand from NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, who worked on both the 2017 experiments and this new study.

"Before irradiation you can't tell it's there, but after irradiation the colour jumps right out at you."

The findings don't count as a definitive guarantee that Europa's underground ocean is filled with table salt, but the researchers were able to spot it in regions where the surface ice has been broken up – possibly allowing materials from underneath to rise up.

That's enough to reassess just what Europa's hidden ocean is made of, say the scientists behind the new study, and the sort of life it might potentially be harbouring.

"Magnesium sulfate would simply have leached into the ocean from rocks on the ocean floor, but sodium chloride may indicate the ocean floor is hydrothermally active," says Trumbo.

"That would mean Europa is a more geologically interesting planetary body than previously believed."

The good news is that the NASA Europa Clipper probe is due to launch in the 2020s and will make no fewer than 45 passes of Europa. It should turn up a whole new treasure trove of information that scientists and salt-seekers can pore over.

This is also yet more evidence of how gathering new data and using new techniques can improve our understanding of the wider Universe, even years or decades after the first observations were made.

The research has been published in Science Advances.