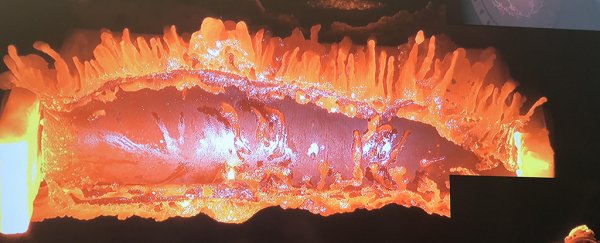

Engineers have captured some eye-popping footage of one of the densest parts of a satellite getting fried into vapour inside an ultra-hot plasma wind tunnel. They destroyed it in the name of science, of course.

The researchers from the European Space Agency (ESA) wanted to better understand how satellites burn up in Earth's atmosphere as they fall from orbit. Using this knowledge could help in protecting all of us from huge chunks of flaming metal hitting the ground.

While a lot of space debris gets entirely burned up in the atmosphere on re-entry, some of it doesn't, and every now and again the objects that survive are big enough to do some serious damage to people, wildlife, and property.

The object destroyed in this experiment was a 4 cm x 10 cm (1.6 inch x 3.9 inch) magnetotorquer, an instrument that interacts with Earth's magnetic field to keep its satellite stable and correctly orientated.

It didn't stand much chance in the plasma wind tunnel at the DLR German Aerospace Centre in Cologne – as the name suggests, it's a wind tunnel that uses an electromagnetic field for heating up a gas to the point of turning into plasma, in this case to simulate a device's trip through Earth's upper atmosphere.

With temperatures inside the tunnel reaching several thousands of degrees Celsius, the experiment gave scientists some useful data points to reference against their models and previous studies.

"We observed the behaviour of the equipment at different heat flux set-ups for the plasma wind tunnel in order to derive more information about materials properties and demisability," says ESA Clean Space engineer Tiago Soares.

"The magnetotorquer reached a complete demise at high heat flux level. We have noted some similarities but also some discrepancies with the prediction models."

The testing is part of the bigger Clean Space Initiative, aimed at reducing the level of debris in orbit and ensure that if it does drop from the sky, it doesn't pose a threat.

Regulations in place today are designed to ensure that uncontrolled re-entries of space objects should have less than a 1 in 10,000 chance of injuring anyone on the ground – but there's still a chance, and that risk will rise as the number of objects in orbit increases. (Just look at the Starlink initiative by Elon Musk's SpaceX.)

Magnetotorquers, optical instruments, propellant and pressure tanks, and drive mechanisms are the most likely satellite bits to survive a trip through Earth's atmosphere. As parts fragment and break up, there's a greater chance of injuring someone.

Whether up in orbit or falling down to Earth, space junk is a growing problem than agencies worldwide are attempting to deal with. With private companies getting into space travel too, the need to find a solution is getting more urgent.

Apart from just spectacularly burning stuff, the work done by engineers at the ESA and elsewhere means we're on the case – and if clean space research can involve more cool experiments like this one, then so much the better.