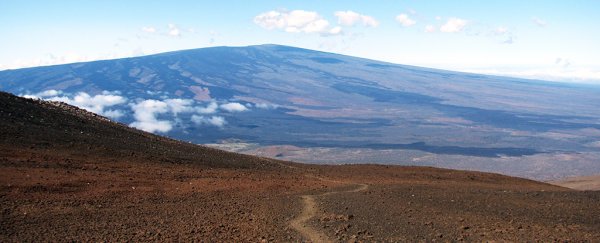

Congratulations Mauna Loa, on the island of Hawaii: you are once more the biggest shield volcano on the planet, without even having done anything. New research suggests the previous record holder, Tamu Massif in the northwest Pacific Ocean, should be disqualified on a technicality.

It all comes down to what you count as a single shield volcano - the large, spread-out type formed by low-viscosity lava. Detailed analysis of the magnetic field over the submerged Tamu Massif suggests it's not a shield volcano as was previously thought, but rather part of a mid-ocean ridge: a much bigger geological structure, formed as oceanic plates shift.

That means Tamu Massif loses the title it's held since 2013, when it was discovered amidst a flurry of scientific excitement, and crowned the largest single volcano in the world – covering roughly the size of New Mexico, or around 310,000 square kilometres (120,000 square miles).

"This is really a large volcanic system, not a single volcano," says geophysicist William Sager from the University of Houston in Texas.

Sager also led the initial study and exploration of Tamu Massif back in 2013, but told Newsweek that he was "nagged" by unanswered questions after the publication of the original paper in Nature Geoscience.

In the new research, Sager and his colleagues found magnetic anomalies deep in the volcano, suggesting Earth's magnetic field flipped at least once during its formation. As these flips happen over thousands or millions of years, the implication is that Tamu Massif was not formed from a single eruption… and is therefore not a regular shield volcano.

That would help explain how Tamu Massif formed at the meeting point of three spreading mid-ocean ridges, and matches up with the magnetic anomalies at the plate boundaries.

And the team of scientists did their due diligence. They analysed some 4.6 million magnetic field readings taken by various ships over the past 54 years. That data was linked to more magnetic readings linked to GPS locations taken by the research vessel Falkor to build up a magnetic map.

If geological features had feelings, the Tamu Massif could still content itself with the knowledge that it's part of the largest volcanic system in the world; it's just not the biggest single shield volcano.

"The largest volcano in the world is really the mid-ocean ridge system, which stretches about 65,000 kilometres [40,000 miles] around the world, like stitches on a baseball," says Sager.

Besides reclassifying Tamu Massif, the research has other important implications in regards to how oceanic plateaus are formed. It was understood that plateaus this big could not be produced by seafloor spreading, where volcanic activity creates oceanic crust by pushing it out from a central eruption.

Tamu Massif offers up evidence to the contrary, and hints that oceanic plateau formations are not as similar to continental flood basalts – the results of volcanic eruptions on land – as previously thought.

As for disproving his own original hypothesis that Tamu Massif was the world's biggest shield volcano, Sager has a great message to share.

"Science is a process and is always changing," says Sager. "There were aspects of that explanation that bugged me, so I proposed a new cruise and went back to collect the new magnetic data set that led to this new result."

"In science, we always have to question what we think we know and to check and double check our assumptions.

"In the end, it is about getting as close to the truth as possible – no matter where that leads."

The research has been published in Nature Geoscience.