Celiac is a chronic autoimmune disease that can have serious long-term consequences for people whose small intestine is affected by ingesting gluten. But because it's an elusive and mysterious condition, it takes about four years for the average person to get properly diagnosed - and the tests can get pretty invasive.

As the incidence of celiac continues to rise, a simple diagnostic blood test is desperately needed. And right now, some of the world's leading celiac experts are working on just that.

Conducting a dozen clinical studies in Australia, New Zealand, and the United States, the international team has discovered a distinct immune marker in the blood of nearly all study participants diagnosed with celiac. And this inflammatory response appears within mere hours of gluten exposure.

The results are so promising, the researchers are already considering the possibility of a faster and easier diagnosis.

"For the many people following a gluten-free diet without a formal diagnosis of coeliac disease, all that might be required is a blood test before, and four hours after, a small meal of gluten," says Jason Tye-Din, a gastroenterologist and celiac researcher at the Royal Melbourne Hospital and the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research.

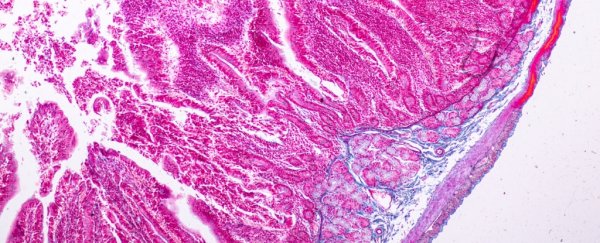

"This would be a dramatic improvement on the current approach, which requires people to actively consume gluten for at least several weeks before undergoing an invasive procedure to sample the small intestine."

While blood tests that can screen for celiac disease do currently exist, they require people to regularly eat gluten for weeks beforehand; this can be a lengthy and uncomfortable process, and there's still a small chance the test won't indicate the disease.

Currently, the only way to confirm a celiac diagnosis is through a biopsy of the small intestine after blood tests have indicated the person might have it.

If we could change all that to a simple set of two blood tests and just one meal with gluten, many lives could change for the better.

During the studies, Tye-Din and his colleagues placed volunteers with celiac on a one-off gluten food challenge. After receiving an injection of gluten peptides under the skin or a mixed drink of wheat flour - either a quarter or a half of an average person's daily intake - the team noticed a rapid and coordinated spike in several immune chemicals known as cytokines.

"The systemic cytokine release observed provides definitive evidence of rapid immune activation within 2 hours after administering gluten peptides in almost all [patients]," their paper concludes.

Screening for up to 18 cytokines, the researchers showed that IL-2 was one of the earliest cytokines to rise and reach peak levels, and its spike was the highest of them all. IL-8 was another cytokine that showed a similar response.

When participants were given the upper dose of gluten, their symptoms of nausea and vomiting increased, and those with more severe bouts had higher plasma concentrations of IL-2.

"The unpleasant symptoms associated with the disease are linked to an increase in inflammatory molecules in the bloodstream, such as interleukin-2 (IL-2), produced by T cells of the immune system," says Robert Anderson, chief scientific officer of ImmusanT Inc, a company working on immune therapies for several autoimmune diseases.

"This response is similar to what happens when an infection is present, however for people with coeliac disease, gluten is the trigger."

Several members of the research team work at ImmusanT, and the company is currently developing a peptide-based 'vaccine' intended to work as immunotherapy for celiac patients; the peptides used in this study were, in fact, the same mixture as this vaccine.

The researchers noted cytokine levels in their patients during phase 1 trials of their vaccine, and decided to investigate further and "characterise systemic cytokine profiles and their relation to acute symptoms in celiac disease patients after reactivation of gluten immunity".

Now, it really looks like they're on to something, although we'll have to wait and see if this potential blood test becomes widely accessible to patients.

The research has been published in Science Advances.