This September, as the world takes a stand on climate change like never before, let's spare a thought for those who helped set the stage. The history of climate science stretches back nearly two hundred years, and in all that time, few women have been memorialised in the discipline.

Just ten years ago, Eunice Foote was a name and face all but forgotten, but in 2019, on her 200th birthday, a handful of scientists are determined to keep her memory alive.

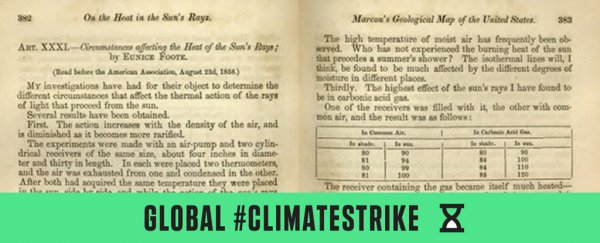

Today, no photographs of this pioneering woman have been found; some of the only evidence of her life comes from a paper in the American Journal of Science, published in 1856.

Foote, a women's rights campaigner with a keen interest in science, had written the paper to be presented at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS). It was a report on the heat-trapping nature of carbon dioxide, based on a simple experiment she had conducted, and its results led her to speculate something revolutionary: higher levels of CO2 would lead to warmer temperatures on Earth.

"An atmosphere of that gas would give to our earth a high temperature," she wrote, "and if as some suppose, at one period of its history the air had mixed with it a larger proportion than at present, an increased temperature from its own action as well as from increased weight must have necessarily resulted."

The idea is eerily prophetic, but at the time, it went largely ignored. After it was presented, only a short page and a half paper were published in the journal, followed by a brief printed summary of her research a year later.

"[T]he experiments of Mrs. Foot afford abundant evidence of the ability of woman to investigate any subject with originality and precision," reads a column from the 1856 issue of Scientific American.

And then Foote's work simply slipped into oblivion.

So it remained for over 150 years. When her ideas were at last re-discovered in 2011 by Ray Sorenson, a retired petroleum geologist, he knew enough about climate science to realise their significance.

Foote, it seems, had published her paper three years before physicist John Tyndall - now considered one of the founding fathers of climate science - confirmed the exact same thing.

"I recognised that it was something that had been missed by historians," Sorenson told Think Progress, "and I felt she deserved recognition."

Today, Sorenson is not the only one trying to preserve Foote's memory.

Katharine Hayhoe, a prominent climate scientist, has been digging into Foote's past for a few years now, as has Liz Foote, a member of the family and a scientist in her own right. Annarita Mariotti, an ocean and atmospheric scientist at NOAA, physicist John Perlin and author Katharine Wilkinson have also joined the fight in promoting Foote's forgotten achievements.

From what we know so far, it's thought that Foote got her paper published, in large part, because her husband was a member of the AAAS. In the mid-1800s, it wasn't uncommon for a paper to be read by a proxy and while it was possible for women to speak at these meetings, it is worth noting that in this case a male professor spoke on Foote's behalf.

"Science was of no country and of no sex," the professor began before reading her results. "The sphere of woman embraces not only the beautiful and the useful, but the true."

Foote's experiment was nowhere near as sophisticated nor as controlled as Tyndall's later research. Her simple set-up involved filling separate glass jars with water vapour, carbon dioxide, and air, and then comparing their ability to heat up.

Tyndall, on the other hand, had rigorous scientific training with access to expensive, high quality equipment, and his findings confirmed what Foote could only speculate.

Whether he knew about Foote or her ideas remains unknown.

"There was a bit of luck involved," Hayhoe told Climate Change News, "but I think it is amazing that she connected the dots and came to a conclusion that subsequent science has proved to be correct."

As a woman, Foote's access to higher education and scientific institution was limited and she faced great sexism (Tyndall himself once wrote that women had "more feeling and less intellect than men"). But she was right on the brink of a major cultural shift, which she herself was helping to lead.

In her time, Foote was a central figure in the American suffragette movement and her name appears fifth on the declaration from the first US women's rights convention at Seneca Falls. She was also one of the only women practising science at the time.

Remembering Eunice Foote's achievements is to remember not only how far climate science has come, but also how far women have come. Her family member and marine biologist Liz Foote told Audubon Magazine that her ancestor's story is an inspiration and a reminder that "we need to work harder to support women in science so they stay in science."

These days, there are more women in the field of climate science than ever before, but even though great progress has been made, too many female scientists still struggle to make themselves heard in a male-dominated discipline.

The IPCC is home to some of the most recognised climate scientists in the world, but a recent survey among 100 women in its ranks reveals that many still feel poorly represented and think their gender is an important barrier to their full participation.

From 1990 to 2018, the proportion of female authors on IPCC reports increased only modestly, from less than 5 percent to more than 20 percent.

"I found Foote's story inspiring and very relevant in today's world," Mariotti told Climate.gov.

"It is a reminder of the struggle that women have gone through to emerge in science and society. Her story is also a reminder that basic elements of climate science, like the warming potential of carbon dioxide, were already being demonstrated over 150 years ago."

This article is part of ScienceAlert's special climate edition, published in support of the global #ClimateStrike on 20 September 2019.