We know that Leonardo da Vinci was a genius who was well ahead of his time, but even the great man himself might have struggled to believe that engineers would still be marvelling over his creations some 500 years later.

Engineers from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) have analysed a bridge designed by da Vinci in 1502. Drawn up for Sultan Bayezid II, head of the Ottoman Empire, the huge bridge was intended to connect Istanbul and its neighboring city Galata.

In the end, da Vinci's design wasn't used, but the MIT team has carefully modelled the polymath's design, finding it to be structurally sound – no mean feat, considering it would've been the world's longest bridge at the time, by some distance.

"It's incredibly ambitious," says structural engineer Karly Bast, from MIT. "It was about 10 times longer than typical bridges of that time."

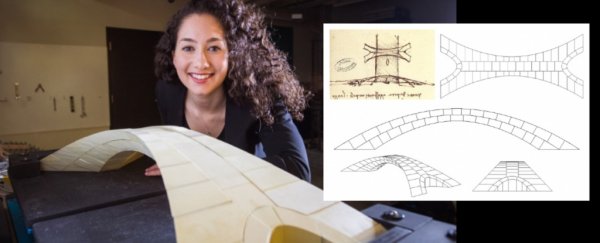

Da Vinci's sketch (top left) with modern-day diagrams. (Karly Bast and Michelle Xie)

Da Vinci's sketch (top left) with modern-day diagrams. (Karly Bast and Michelle Xie)

Using surviving documentation, and knowledge about the construction materials and methods of the time, the team found that the 280-metre (919-foot) long bridge would have been able to stand and remain stable.

While the researchers haven't yet had a peer-reviewed paper published about their work, they did put together a 1:500 scale model to put to a rigorous set of tests.

The crafted 126 separately created, 3D-printed blocks, then put them together like a jigsaw: at 1:500 scale, the model ended up at around 81 centimetres or 32 inches long.

(Gretchen Ertl)

(Gretchen Ertl)

One of the most impressive parts of the bridge design is that it's all held together without any fasteners or mortar to connect the blocks.

"It's all held together by compression only," says Bast. "We wanted to really show that the forces are all being transferred within the structure."

Rather than following the contemporary trend for bridges with semicircular arches – which would have required numerous piers along the bridge – da Vinci instead went for a single, enormous, flattened arch.

It had to be high enough to allow sailboats to pass under, while maintaining essential rigidity, especially against lateral motions. To counter these motions, da Vinci envisioned splayed abutments on each side of the bridge, which are structures that steady the bridge in the same way that someone might spread their feet to avoid swaying.

Extra stabilisation features were added by da Vinci to guard against the earthquakes that were known to happen in the area, and again the scale model testing showed that these would have worked very well.

The materials and construction methods that we've developed since da Vinci's time mean there are now better designs to make use of than this one, but it's still a phenomenal bit of engineering, that underlines the brilliance of da Vinci's mind.

The scale model was based on a small sketch in one of da Vinci's notebooks – what we don't know is just how long he took to develop it. It's possible that this incredibly smart design was actually the result of just a few minutes of work.

"Was this sketch just freehanded, something he did in 50 seconds, or is it something he really sat down and thought deeply about?" says Bast. "It's difficult to know. He knew how the physical world works."

The research is being presented at the conference of the International Association for Shell and Spatial Structures in Barcelona.