The leading hypothesis on the cause of Alzheimer's is looking shaky, following a new study that tracked the disease's early progress in hundreds of volunteers.

For more than 30 years, amyloid plaques have been primary suspects in the cause of dementia. While the potentially toxic accumulations of protein still seem to be related, this research is part of a growing body of evidence that suggest they're actually latecomers to the disease rather than an early trigger.

Scientists from University of California San Diego School of Medicine and Veterans Affairs San Diego Healthcare System came to this conclusion after analysing brain scans of individuals showing subtle signs of cognitive decline.

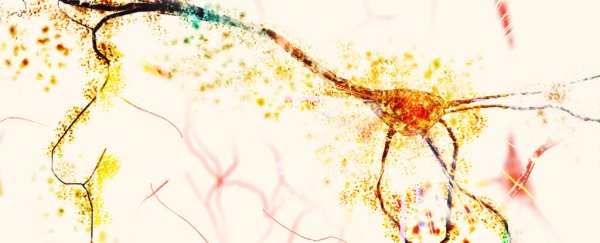

According to the amyloid cascade hypothesis, knotted fragments of a common protein found in cell membranes are responsible for the degeneration behind Alzheimer's symptoms of memory loss and confusion.

Since its proposal back in the eighties, the explanation has gathered support in the form of studies showing how aggregates of beta-amyloid have a debilitating effect on health of neurons.

But as any good detective knows, identifying a nefarious suspect at the scene of the crime isn't the same thing as proving responsibility.

With so many attempts to remove the clumps in experiments falling well short of expectations, researchers have started to think amyloid plaques might be red herrings after all.

"The scientific community has long thought that amyloid drives the neurodegeneration and cognitive impairment associated with Alzheimer's disease," said psychiatrist Mark W. Bondi from UC San Diego School of Medicine.

"These findings, in addition to other work in our lab, suggest that this is likely not the case for everyone."

For more than 15 years, the team has been working as part of the Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative, which measures changes associated with Alzheimer's disease in hundreds of volunteers in the hope of finding better methods of early diagnosis.

This latest research involved 747 participants from the initiative – 305 classed as cognitively normal, with the remainder diagnosed with some form of cognitive impairment.

One form of testing found 289 had a mild form of decline, but a more specific set of objective psychological assessments determined 153 had subtle cognitive difficulties – indicating they had very early stages of the disease.

A close look at positron emission tomography (PET) scans taken over four years revealed individuals who were objectively assessed for very early, subtle signs of impairment did, in fact, accumulate amyloid at a faster rate than clinically normal participants.

Plaques were also found to accumulate faster over time, as expected in those who might receive an Alzheimer's diagnosis.

But comparisons with clinically normal brains found no statistical difference in plaque concentrations during the condition's earliest stages, indicating the protein clumps weren't necessarily responsible for kicking off the condition.

And interestingly, while the study found those with mild cognitive impairment had comparatively high levels of amyloid in their brains in early scans, these levels didn't increase with time.

Identifying marked differences between the different assessment groups adds weight to arguments that a specific set of measures can provide a clear heads-up on the risk of developing dementia later in life.

Clinical investigators are currently divided on the best sets of tools to use to diagnose Alzheimer's as early as possible, with teams looking into blood tests and subjective reporting. But this team think objective neuropsychological assessments are the way to go for even earlier detection.

"While the emergence of biomarkers of Alzheimer's disease has revolutionized research and our understanding of how the disease progresses, many of these biomarkers continue to be highly expensive, inaccessible for clinical use or not available to those with certain medical conditions," says psychiatrist and lead researcher Kelsey Thomas from the UC San Diego School of Medicine.

So the important question now is if amyloid plaques are looking less likely as agents of destruction, then what is to blame? Fortunately, scientists have a pretty good lead.

A second suspect – tangled knots of a protein called tau – is increasingly gaining attention as a potential disease driver.

In fact, another new study published this week used a novel kind of imaging to map tau in brains, finding it did a far better job of explaining the pathology than amyloid.

Some 50 million people around the world are living with Alzheimer's, a statistic that is sure to go up as populations age. Early diagnosis will be vital if we're to keep those numbers down but we're also going to need therapies that work as hoped.

It's looking more and more likely that reducing amyloid protein plaques might not be among them.

This research was published in Neurology.