A mysterious repeating radio signal from space revealed last year is now the fifth fast radio burst to be tracked back to its source galaxy.

It's a location unlike any of the others, and astronomers are having to rethink their previous assumptions about how these signals are generated.

The origin of this repeating signal is a spiral galaxy, located 500 million light-years from Earth, making it the closest known source of what we call fast radio bursts (FRBs) yet.

And the FRBs are emanating specifically from a region just seven light-years across - a region that's alive with star formation.

"This object's location is radically different from that of not only the previously located repeating FRB, but also all previously studied FRBs," said astronomer Kenzie Nimmo of the University of Amsterdam in the Netherlands.

"This blurs the differences between repeating and non-repeating fast radio bursts. It may be that FRBs are produced in a large zoo of locations across the Universe and just require some specific conditions to be visible."

Fast radio bursts are among the Universe's strangest mysteries. They are extremely brief spikes in electromagnetic radiation detected by radio telescopes, lasting no more than a few milliseconds at most. But in that time, they can discharge more energy than 500 million Suns.

Most of the fast radio bursts detected to date have only appeared once. These are impossible to predict, which makes them extremely difficult to trace - to date, only three have had their origin localised to a galaxy.

But in recent years, we've begun to find FRBs that repeat - popping off repeat signals with no discernible pattern - and in 2017, scientists managed to track down the origin of one of them.

Then last year, scientists announced that the CHIME experiment in Canada had detected a massive eight new repeating FRBs, bringing the number of known repeaters to a total of 10. It is one of these new repeaters - a signal called FRB 180916.J0158+65 (FRB 180916 for short) - that astronomers have now traced.

An international team of astronomers used eight telescopes participating in the European Very Long Baseline Interferometry Network to conduct follow-up observations in the direction of FRB 180916. Over the course of five hours, they detected four more bursts - which allowed them to home in on the source of the signal.

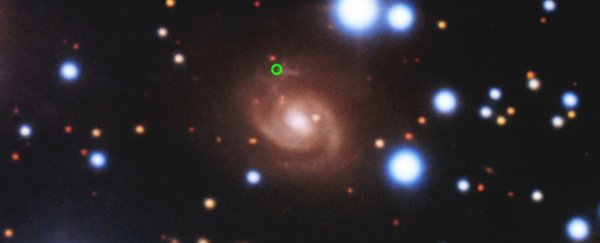

And that led them to a normal spiral galaxy called SDSS J015800.28+654253.0.

The first repeating fast radio burst to be localised was FRB 121102. It was found to be emanating from a dwarf galaxy poor in metals over 3 billion light-years away, and the signal had been distorted by something called the Faraday effect, which occurs when electromagnetic radiation interacts with a magnetic field.

This suggested that FRB 121102 was produced in an extreme environment, like the region around a supermassive black hole at the galactic centre. Interestingly, it, too, seemed to be close to a star-forming region.

The three other non-repeating FRBs, on the other hand, were found in much more conventional galaxies - but only one of them was near a star-forming region.

FRB 180916 was not nearly as distorted by the Faraday effect as FRB 121102, which indicates that its location was not as magnetic; and it was found pretty far from the galactic centre.

"The multiple flashes that we witnessed in the first repeating FRB arose from very particular and extreme conditions inside a very tiny (dwarf) galaxy," said astronomer Benito Marcote of the Joint Institute for VLBI ERIC.

"This discovery represented the first piece of the puzzle but it also raised more questions than it solved, such as whether there was a fundamental difference between repeating and non-repeating FRBs. Now, we have localised a second repeating FRB, which challenges our previous ideas on what the source of these bursts could be."

Possible explanations for FRBs put forward to date include neutron stars, black holes, pulsars with companion stars, imploding pulsars, a type of star called a blitzar, a connection with gamma-ray bursts (which we now know can be caused by colliding neutron stars), and magnetars emitting giant flares.

This research has not answered that burning question, but it could be starting to help rule out what it isn't.

"With the characterisation of this source, the argument against against pulsar-like emission as origin for repeating FRBs is gaining strength," said Ramesh Karuppusamy of the Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy in Germany.

"We are at the verge of more such localisations brought about by the upcoming newer telescopes. These will finally allow us to establish the true nature of these sources."

The research has been published in Nature.