A 120 million-year-old fossil is helping paleontologists bridge the 'phantom' evolutionary leap between feathered dinosaurs and modern birds.

Dubbed "the dancing dragon", or Wulong bohaiensis, this newly described species is a strange mix between bird and dinosaur, ancient and new.

First discovered in China more than a decade ago, in one of the world's richest fossil deposits, the ancient animal's beautifully preserved bones have only recently received closer inspection.

The Jiufotang Formation, where the fossil was found, belongs to the Jehol group - known for its incredible variety of animals, it's considered one of the earliest habitats where dinosaurs, birds, and bird-like dinosaurs co-existed. But even amongst stiff competition, the Wulong fossil is one of a kind.

(Poust et al., The Anatomical Record, 2020)

(Poust et al., The Anatomical Record, 2020)

Experts from China and the United States now think this dancing specimen is one of the earliest relatives of velociraptors, and a crucial stepping stone in the obscure dinosaur-to-bird transition.

Smaller than a raven but larger than a crow, this new species would have looked somewhat like a tiny feathered raptor, equipped with four wing-like limbs and a super long, double-plumed tail. And yet, there was something strange about its age.

"The specimen has feathers on its limbs and tail that we associate with adult birds, but it had other features that made us think it was a juvenile," says paleontologist Ashley Poust from San Diego Natural History Museum.

An X-ray of the specimen, showing wrist and vertebra detail on the right. (Poust et al., The Anatomical Record, 2020)

An X-ray of the specimen, showing wrist and vertebra detail on the right. (Poust et al., The Anatomical Record, 2020)

The combination was puzzling. Feathers were once thought unique to birds, but thanks to recent discoveries - many of which came from the same Chinese province - it now appears many of these key avian features evolved much earlier on, maybe even before dinosaurs.

In fact, velociraptor embryos are said to look "almost identical" to the world's first birds.

Examining several bones from the Wulong specimen, Poust and colleagues determined that despite its mature-looking feathers, this particular dancing dinosaur was, in fact, a juvenile - roughly a year old.

"The presence of such elaborate structures in the similarly sized, relatively somatically immature Wulong demonstrates that non-avian dinosaurs had a very different strategy of plumage development than their living relatives," the authors write.

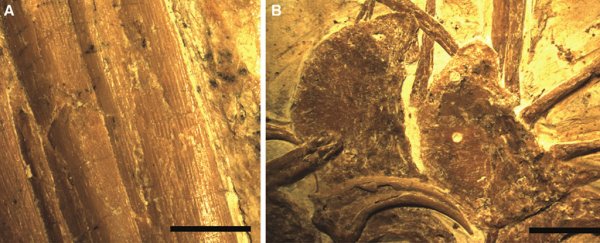

Skull with lower jaws. (Poust et al., The Anatomical Record, 2020)

Skull with lower jaws. (Poust et al., The Anatomical Record, 2020)

Most modern birds, for instance, do not grow their plumage quite that quickly, especially those cumbersome tail-feathers usually reserved for mating. Wulong's tail, on the other hand, practically doubles the dinosaur's length, and its feathers appear to have developed well before sexual maturity.

"Either the young dinosaurs needed these tail feathers for some function we don't know about, or they were growing their feathers really differently from most living birds," explains Poust, who now works at the San Diego Natural History Museum.

To work out the details, the team compared the remains to samples of a dinosaur from the Sinornithosaurus genus. Those bones were also large and adult-looking, but turned out to not be fully grown either. Together, the team warns against making determinations of age based on observation alone.

While bone histology can be destructive to a skeleton, the researchers argue it is also one of the most dependable methods and the best way for us to understand key discoveries.

"The new dinosaur fits in with an incredible radiation of feathered, winged animals that are closely related to the origin of birds," says Poust.

"Studying specimens like this not only shows us the sometimes surprising paths that ancient life has taken, but also allows us to test ideas about how important bird characteristics, including flight, arose in the distant past."

The study was published in The Anatomical Record.