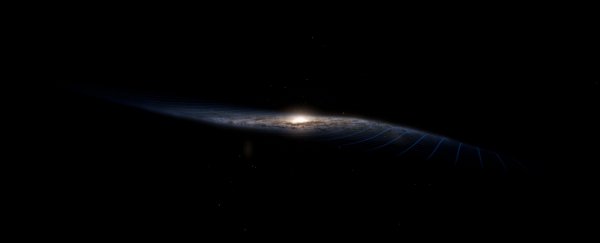

The Milky Way isn't like other barred spiral galaxies. Instead of a nice, tidy flat disc, it has a kink in its spine, a twist in its swagger. As we have long known, and two separate studies recently confirmed, the Milky Way is seriously warped around the edges, a strange idiosyncrasy that's been puzzling astronomers for years.

Now a new analysis of data from the Gaia mission has ponied up an explanation: it's the result of a collision with a smaller galaxy sometime in the Milky Way's murky past.

It's unclear when, or which galaxy. But the way the warp whirls around the galactic centre seems like it could only have been caused by a relatively recent, or even ongoing, kerfuffle with one of the Milky Way's satellite galaxies.

The Gaia mission has already done great work revealing our galaxy's somewhat violent past.

A collision with another galaxy 8 to 11 billion years ago puffed up the Milky Way's thick disk, filling it with stars. An encounter with a ghost galaxy millions of years ago left ripples in the Milky Way's hydrogen. And let's not forget a smash-up with a galaxy called the Gaia Sausage, which left stars reeling about in peculiar orbits.

The Gaia satellite was launched in 2013, and has been collecting data ever since to produce the most accurate 3D map yet of the Milky Way. It's carefully studying the proper motions, radial velocities and distances of the stars to determine where everything is, and how it's moving around.

"It's like having a car and trying to measure the velocity and direction of travel of this car over a very short period of time and then, based on those values, trying to model the past and future trajectory of the car," said astronomer Ronald Drimmel of the Turin Astrophysical Observatory in Italy.

"If we make such measurements for many cars, we could model the flow of traffic. Similarly, by measuring the apparent motions of millions of stars across the sky we can model large scale processes such as the motion of the warp."

By carefully analysing this data for 12 million stars, a team of astronomers found that the warp in the Milky Way's disc isn't just sitting in one place. It's moving around the galactic centre, just like the stars - but at a different velocity.

While that velocity is slower than the stars, it's much faster than other previous explanations for the warp - such as the effect of a dark matter halo, or an intergalactic magnetic field - would allow.

"We measured the speed of the warp by comparing the data with our models. Based on the obtained velocity, the warp would complete one rotation around the centre of the Milky Way in 600 to 700 million years," said astronomer Eloisa Poggio of the Turin Astrophysical Observatory. (For comparison, the Sun orbits the galactic centre every 220 million years.)

"That's much faster than what we expected based on predictions from other models, such as those looking at the effects of the non-spherical halo."

That means something more powerful must have given the warp a shove; like, oooh, say… another galaxy bumping into the Milky Way, for instance.

So, which galaxy? Well, that's yet to be discovered. The researchers think it could be the Sagittarius Dwarf Spheroidal Galaxy. It's on a pretty close orbit with the Milky Way, and it's historically proven pretty disruptive.

Astronomers believe that it has passed through the plane of the Milky Way more than once, shaping its rings, and there's evidence that it has also messed with the stars in the centre of the galactic disc.

Eventually, the Milky Way will emerge victorious, absorbing the Sagittarius Dwarf Spheroidal Galaxy and incorporating its globular clusters - but that day is a long way away.

Future analysis, and the next release of Gaia data scheduled for sometime later this year, could help figure out if this galaxy is the culprit, so we'll have to wait and see.

The research has been published in Nature Astronomy.