Some chimpanzees might be growing hard-hearted with age. A curious little bone has been found forming in the heart tissue of several chimpanzees, according to a newly published study.

The size of this mineralised tissue, measuring no more than a few millimetres, appears to vary among individuals; but on the whole, researchers say it appears to be an os cordis - a type of heart bone usually found in large ruminants, such as cattle and buffalo, but also present in camels and even otters.

No such thing has ever been identified in chimps before, or any other great ape for that matter, leading the research team to speculate about human anatomy, too.

"The discovery of a new bone in a new species is a rare event, especially in chimps which have such similar anatomy to people. It raises the question as to whether some people could have an os cordis too," says anatomist Catrin Rutland from the University of Nottingham.

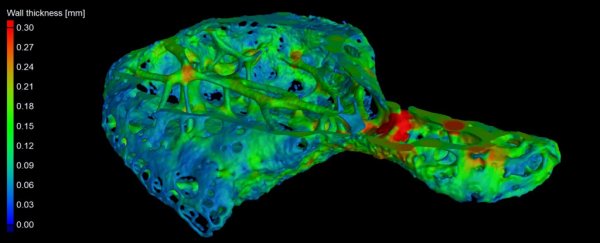

Using high-resolution scans to analyse the cardiac skeleton structure (dense connective tissue supporting the heart) of great apes for the first time, researchers noticed calcifications growing in the hearts of some chimpanzees.

Closely tied to age, the eldest female among the group, coming in at 59 years old, was found with several sites of hardening within the great vessels of her heart.

Further analysis of the tissue at microscopic levels revealed these structures were sometimes made entirely of bone, sometimes of cartilage, and other times were somewhere in between the two tissue types.

Given the relatively small scope of such a study, it's possible this is merely an anatomical peculiarity among some chimps, but the researchers have reason to suspect otherwise.

In humans, mineralisation of the cardiac skeleton is usually due to age, and is associated with cardiovascular disease. While chimps may not be as prone to coronary artery issues as our own species, heart disease still affects nearly 70 percent of captive adult chimps.

The most common type of heart disease in chimps is idiopathic myocardial fibrosis (IMF), which is marked by an accumulation of fibrous connective tissue associated with arrhythmia - atypical heart rhythms - and sudden cardiac arrest.

Out of all 16 hearts the team assessed in this study, only 3 chimps showed no evidence of IMF in their hearts, and didn't have any hyperdense areas, either. On the other hand, all chimp hearts affected by IMF showed bone or cartilage formation, and increased connective tissue nearby.

"In the remaining seven hearts, hyperdense areas were detected and were compatible with areas of mineralisation or bone formation (shown as very bright regions in the images)," the authors write.

In four of these cases, the location and size of this structure fell in just the same spot as an os cordis.

"The significant association between the presence of an os cordis and high levels of IMF suggests that the presence of an os cordis in this species may be a pathological finding or marker rather than an anatomical feature," the paper concludes.

The pathology of IMF in great apes is poorly understood, but if the authors are right and this bone is somehow involved, it's crucial we find out more. Chimpanzees are an endangered species and cardiovascular disease is one of the biggest threats to their lives in captivity - and possibly also in the wild.

While comparing the scans, researchers found one heart that contained a so-called cartilage cordis, which looked like it might have been a precursor to further bone formation.

Whether or not this is a bad thing for the animals remains unclear. The exact function of os cordis hasn't been figured out yet in other species, and even in cases where it develops with age - as it does in otters - it's not always harmful, and could actually protect the heart valves.

"The clinical and functional implications of the presence of cartilage and bone tissue in the chimpanzee cardiac skeleton remain to be elucidated," the authors of this new research write.

"[W]hether the presence of cartilage formation or ossification [bone growth] within the cardiac skeleton of chimpanzees further increases the chances of arrhythmic events is, as yet, unknown."

The study was published in Scientific Reports.