The predation of livestock by carnivores, and the retaliatory killing of carnivores as a result, is a major global conservation challenge. Such human-wildlife conflicts are a key driver of large carnivore declines and the costs of coexistence are often disproportionately borne by rural communities in the global south.

While current approaches tend to focus on separating livestock from wild carnivores, for instance through fencing or lethal control, this is not always possible or desirable. Alternative and effective non-lethal tools that protect both large carnivores and livelihoods are urgently needed.

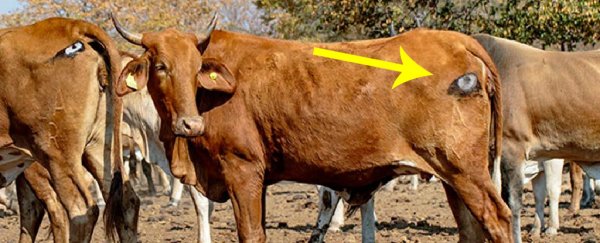

In a new study we describe how painting eyes on the backsides of livestock can protect them from attack.

Many big cats – including lions, leopards, and tigers – are ambush predators. This means that they rely on stalking their prey and retaining the element of surprise. In some cases, being seen by their prey can lead them to abandon the hunt.

We tested whether we could hack into this response to reduce livestock losses to lions and leopards in Botswana's Okavango delta region.

This delta, in north-west Botswana, has permanent marshlands and seasonally flooded plains which host a wide variety of wildlife. It's a UNESCO world heritage site and parts of the delta are protected. However, though livestock are excluded, the cordon fence is primarily intended to prevent contact and disease transmission between cattle and Cape buffalo.

Large carnivores, and other wildlife including elephants, are able to move freely across it, and livestock losses to large carnivores are common in the area. In response, lethal control through shooting and poisoning can occur.

While the initial focus of the study was ambush predators generally, it soon became clear that lions were responsible for most of it. During the study, for instance, lions killed 18 cattle, a leopard killed one beast, and spotted hyaenas killed three.

Ultimately, our study found that lions were less likely to attack cattle if they had eyes painted on their rumps. This suggests that this simple and cost-effective technique can be added to the coexistence toolbox, where ambush predators are involved.

Eye-catching solution

Conflict between farmers and wildlife can be intense along the borders of protected areas, with many communities bearing significant costs of coexisting with wildlife. The edge of the Okavango delta in Botswana is no exception, where farmers operate small non-commercial livestock enterprises.

Livestock rub shoulders with lions, leopards, spotted hyaenas, cheetahs, and African wild dogs.

To protect the cattle, herds (anything between about six and 100 individual cattle) are kept within predator-proof enclosures overnight. However, they generally graze unattended for most of the day, when the vast majority of predation occurs.

Working with Botswana Predator Conservation and local herders, we painted cattle from 14 herds that had recently suffered lion attacks. Over four years, a total of 2,061 cattle were involved in the study.

Before release from their overnight enclosure, we painted about one-third of each herd with an artificial eye-spot design on the rump, one-third with simple cross-marks, and left the remaining third of the herd unmarked. We carried out 49 painting sessions and each of these lasted for 24 days.

The cattle were also collared and all foraged in the same area and moved similarly, suggesting they were exposed to similar risk. However the individuals painted with artificial eye-spots were significantly more likely to survive than unpainted or cross-painted control cattle within the same herd.

In fact, none of the 683 painted "eye-cows" were killed by ambush predators during the four-year study, while 15 (of 835) unpainted, and 4 (of 543) cross-painted cattle were killed.

Nenguba Keitsumetsi demonstrates the technique to farmer, Rra Ketlogetswe Ramakgalo. (Bobby-Jo Photography)

Nenguba Keitsumetsi demonstrates the technique to farmer, Rra Ketlogetswe Ramakgalo. (Bobby-Jo Photography)

These results supported our initial hunch that creating the perception that the predator had been seen by the prey would lead it to abandon the hunt.

But there were also some surprises.

Cattle marked with simple crosses were significantly more likely to survive than unmarked cattle from the same herd. This suggests that cross-marks were better than no marks at all, which was unexpected.

From a theoretical perspective, these results are interesting. Although eye patterns are common in many animal groups, notably butterflies, fishes, amphibians, and birds, no mammals are known to have natural eye-shaped patterns that deter predation. In fact, to our knowledge, our research is the first time that eye-spots have been shown to deter large mammalian predators.

Previous work on human responses to eye patterns however do generally support the detection hypothesis, perhaps suggesting the presence of an inherent response to eyes that could be exploited to modify behaviour in practical situations, such as to prevent human-wildlife conflicts, and reduce criminal activity in humans.

Possible limitations

First, it is important to realise that, in our experimental design, there were always unmarked cattle in the herd. Consequently, it is unclear whether painting would still be effective if these proverbial "sacrificial lambs" were not still on the menu. Further research could uncover this, but in the meantime applying artificial marks to the highest-value individuals within the herd may be most pragmatic.

Second, it is important to consider habituation, meaning that predators may get used to and eventually ignore the deterrent. This is a fundamental issue for nearly all non-lethal approaches. Whether the technique remains effective in the longer term is not yet known in this case.

Protecting livestock from wild carnivores – while conserving carnivores themselves – is an important and complex issue that requires the application of a suite of tools, including practical and social interventions.

While adding the eye-cow technique to the carnivore-livestock conflict prevention toolbox, we note that no single tool is likely to be a silver bullet. Indeed, we must do better than a silver bullet if we are to ensure the successful coexistence of livestock and large carnivores. Nevertheless, as part of an expanding non-lethal toolkit, we hope that this simple, low-cost approach could reduce the costs of coexistence for some farmers.

Dr J Weldon McNutt (Director, Botswana Predator Conservation) and Tshepo Ditlhabang (Coexistence Officer, Botswana Predator Conservation) contributed to this article. ![]()

Neil R Jordan, Lecturer, UNSW; Cameron Radford, PhD Candidate, UNSW, and Tracey Rogers, Associate Professor Evolution & Ecology, UNSW.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.