A giant, catastrophic tsunami in Alaska triggered by a landslide of rock left unstable after glacier melting is likely to occur in the next two decades, scientists fear - and it could happen within the next 12 months.

A group of scientists warned of the prospects of this impending disaster in Prince William Sound in an open letter to the Alaska Department of Natural Resources (ADNR) in May.

While the potential risks of such a landslide are very serious, there remain a lot of unknowns about just how or when this calamity could take place.

What is clear is that glacier retreat in Prince William Sound, along the south coast of Alaska, does seem to be having an impact on mountain slopes above Barry Arm, about 97 kilometres (60 miles) east of Anchorage.

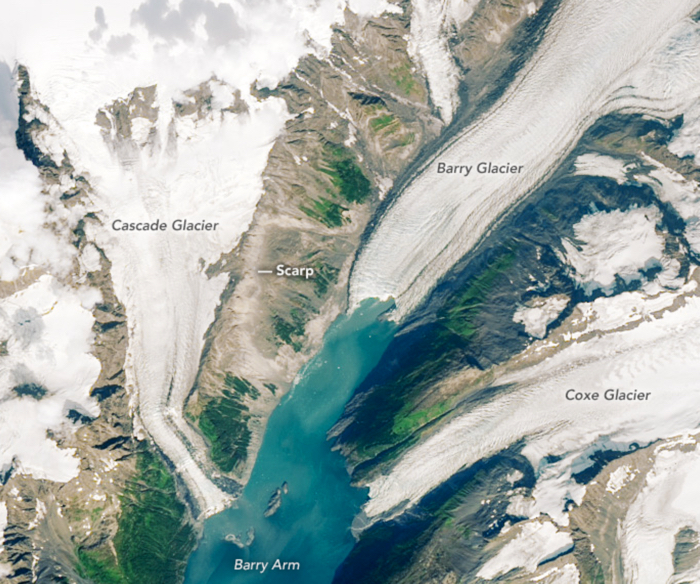

Analysis of satellite imagery suggests that as Barry Glacier retreats from Barry Arm due to ongoing melting, a large rocky scar called a scarp is emerging on the face of the mountain above it.

This indicates an incremental, slow-moving landslide is already taking place above the fjord, but if the rock face were to suddenly give way, the consequences could be dire.

Although it's remote, this is an area that's frequented by commercial and recreational boats, including cruise ships.

Pale scarp lines above Barry Glacier. (Lauren Dauphin/NASA Earth Observatory/USGS)

Pale scarp lines above Barry Glacier. (Lauren Dauphin/NASA Earth Observatory/USGS)

"It was hard to believe the numbers at first," one of the researchers, geophysicist Chunli Dai from the Ohio State University told NASA's Earth Observatory.

"Based on the elevation of the deposit above the water, the volume of land that was slipping, and the angle of the slope, we calculated that a collapse would release 16 times more debris and 11 times more energy than Alaska's 1958 Lituya Bay landslide and mega-tsunami."

If the team's calculations are correct, such a result borders on the unthinkable, because the 1958 episode – likened by eyewitnesses to the explosion of an atomic bomb – is often thought to be the tallest tsunami wave in modern times, reaching a maximum elevation of 524 metres (1,720 feet).

A much more recent slope failure event in 2015 in Taan Fiord to the east produced a tsunami reaching as high as 193 metres (633 ft), and the researchers say these failures can be brought about by numerous causes.

"Slopes like this can change from slow creeping to a fast-moving landslide due to a number of possible triggers," the May report explains.

"Often, heavy or prolonged rain is a factor. Earthquakes commonly trigger failures. Hot weather that drives thawing of permafrost, snow, or glacier ice can also be a trigger."

(Gabe Wolken)

(Gabe Wolken)

Since the report's release earlier in the year, subsequent landslide analysis has suggested little or no movement of land masses on the slope, although in itself that doesn't tell us much, since research shows that the rock face has been shifting since at least 50 years ago, at some points speeding up, while slowing down at others.

While these kinds of subtle variations are still being investigated, the overall view is that the speed of glacier retreat increases the probability of more dramatic slope failures.

"When the climate changes, the landscape takes time to adjust," co-author of the letter and geologist Bretwood Higman from nonprofit Ground Truth Alaska told The Guardian.

"If a glacier retreats really quickly it can catch the surrounding slopes by surprise – they might fail catastrophically instead of gradually adjusting."

Ongoing monitoring by numerous organisations – including ADNR, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, and the US Geological Survey – is keeping tabs on developments at Prince William Sound, to track movements above the Barry Glacier, and to refine predictions of what the fallout from a mega-tsunami would be.

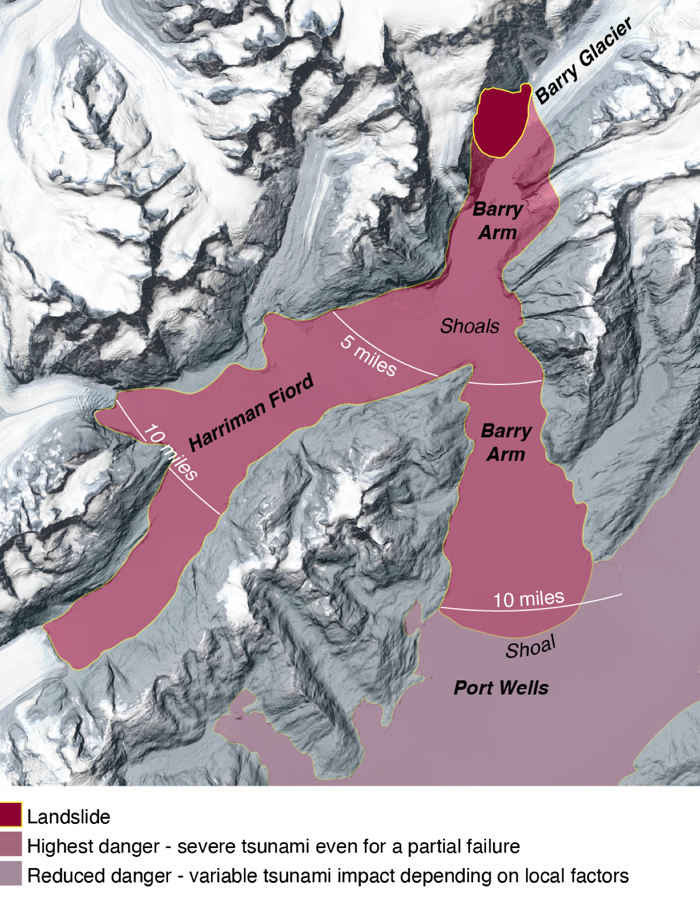

Tsunami projections. (Briggs et al., open letter to ADNR, May 2020)

Tsunami projections. (Briggs et al., open letter to ADNR, May 2020)

Preliminary modelling from the May report, which hasn't yet been peer-reviewed, suggests a tsunami reaching hundreds of feet in elevation along the shoreline would result from a sudden massive failure, propagating throughout Prince William Sound, and into bays and fjords far from the source.

Perhaps the bigger takeaway is that the impacts of relatively rapid glacier retreats in the era of climate change could pose similar kinds of landslide and tsunami threats in many other places around the world, not just in Alaska.

"It's really pretty terrifying," Higman told Columbia University's GlacierHub blog in May, likening the environmental risks to volcanoes – something that humanity has understood to be a dangerous, unpredictable geohazard for much, much longer.

"Maybe we're entering a time now where we need to look at glaciated landscapes with the same kind of glasses."

The findings are available on the ADNR website.