Planning to attend an event but unsure of the COVID-19 risk, and if you should go at all? There's an evidence-based interactive webtool that can help.

Developed by researchers at Georgia Institute of Technology and simple in its design, the online tool uses data updated daily to estimate the chance that one or more people at an event are COVID-19 positive.

Navigating risk can be tricky, especially when the number of COVID-19 cases is changing every day, and infection rates can be starkly different from one place to the next.

This tool uses real-time data on local COVID cases in the US to quantify and visualise the expected risk for gatherings of different sizes: from a dinner party of 10 people, a wedding reception with 100 guests, to a sporting game with 100,000 spectators.

It has also recently been expanded to estimate risk in several European countries, including Italy, Switzerland, and the UK.

"As cases have begun to rise here [in the US] and schools and businesses are reopening, people are asking hard questions," quantitative biologist Joshua Weitz, senior author of a new paper on the tool, told Wired in July.

"Can I send my child into a classroom? Can I safely go into a bar or a restaurant? Answering those questions is the core of what we are trying to do."

Most other interactive maps and dashboards, such as this one from the World Health Organisation (WHO), display COVID-19 case numbers and deaths; by contrast, this tool links data on documented cases in each US state with risk assessments by event size. Having this info can help people, policy makers and health officials assess the daily risk in their area and plan accordingly.

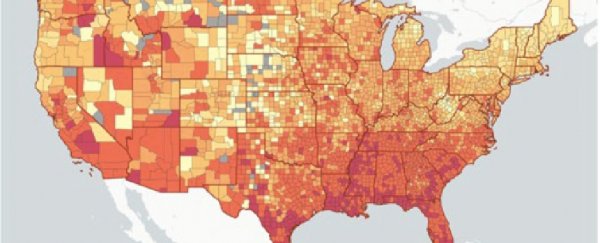

The results are displayed as a heat map where users can compare US states or zoom into their local county, and toggle between events of different sizes to see how the risk escalates as numbers grow.

"By providing a quantitative tool to convey the ongoing risk of the pandemic, we hope to supplement and bolster local public health advisories," the researchers said.

The tool pools real-time data from state public health departments, the COVID Tracking Project, a volunteer organisation collecting data on COVID cases in the US, and the New York Times' open-access dataset of coronavirus cases.

"Our risk calculations tell you only how likely it is that at least one person at any event of a given size is infectious." the researchers write in the study.

"This is not the same as the risk of any person being exposed or infected with COVID-19 at the event."

The risk estimates are based on how many people turn up to an event and how many cases have been detected in that area (in the past ten days), but not their behaviour once they arrive.

The researchers did, however, adjust case numbers in their model to account for the paucity of testing in the US.

"Cases may be under-reported due to testing shortages, asymptomatic 'silent spreaders' and reporting lags," the team explains.

With the available data, the nationwide analysis shows that most US counties share an inevitably high risk with events attended by more than 1,000 people, and a lower risk when events are small (fewer than ten guests). The risk varies much more county-to-county for events with 50 to 150 people.

(Chande et al., Nature Human Behaviour, 2020)

(Chande et al., Nature Human Behaviour, 2020)

Above: Maps visualising the county-level risk of at least one COVID-19-positive person attending an event in the US with 10 (top), 100 (middle) or 1,000 people (bottom).

"The visualised risk maps are intended to inform individuals on the need to take preventative steps to reduce new transmission, for example, by avoiding large gatherings and wearing masks when in close contact with others," the researchers said in their paper.

"As a result, individuals can visualise themselves in a group and decide whether this risk is worth taking."

If you are attending an event, no matter the size, the onus is on everyone there to wear a mask, practise social distancing, and wash their hands regularly.

"Such precautions are still needed even in small events, given the large number of circulating cases," the researchers write.

It should be pointed out though that the model, focusing just on the number of event attendees and recent cases, doesn't take the type of venue into account.

But we know that SARS-CoV-2 spreads through the air, so event planners and health authorities should make the distinction between indoor venues that may have poor ventilation, where super-spreading events are more likely to take place, and outdoor events with plenty of space and fresh air, where the risk is generally lower.

The model also assumes that someone who is COVID-19 positive is just as likely to attend an event as someone without the disease; in reality, the former should follow public health advice and stay at home if they know they have the virus.

Making assumptions like these is part and parcel of modelling; we just need to be aware of them so we understand its limitations.

The biggest uncertainty in the model still remains the actual number of recorded and documented COVID-19 cases, which we can only begin to appreciate with more testing.

The research is published in Nature Human Behaviour and the interactive webtool can be accessed here.