Recently advances have shown that psychedelics like ketamine have powerful potential for treating mental health conditions such as addiction, anxiety, and depression. But psychedelics can come with serious side effects, like cardiac toxicity and their infamous hallucinations.

"Psychedelics are some of the most powerful drugs we know of that affect the brain," said chemist David Olson from University of California. "It's unbelievable how little we know about them."

So University of California neuroscientist Lindsay Cameron, Olsen and colleagues decided to take a closer look and see if they could mess with a psychedelic compound in a way that allows them to keep its useful features, but do away with the more dangerous parts.

After extracting the psychedelic compound ibogaine from the African rainforest shrub Tabernanthe iboga, the researchers used a drug-designing technique called function-orientated synthesis to identify which part of the ibogaine molecule induces structural changes in brain cells in laboratory cultures and animals.

They named their resulting synthetic molecule tabernanthalog (TBG).

Cameron and team then treated alcohol-addicted mice and heroin-addicted rats with TBG. Not only did a single dose allow the mice to stop drinking, the compound had a long-lasting effect on rats trained to self-administer doses of heroin, reducing their tendency to seek out the drug. Even when presented with cues that reminded them of their addiction, the rats generally avoided relapsing.

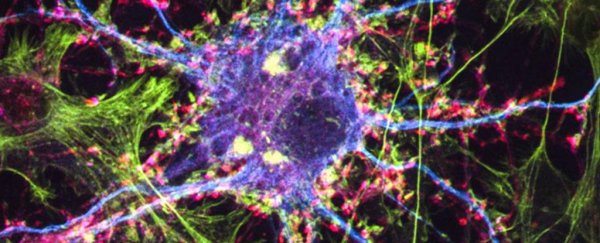

Experiments in zebrafish also showed TBG has a lower toxicity level than the original ibogaine compound. It also doesn't cause mice to twitch their heads in a way that indicates they're hallucinating, and it appears to be increasing connectivity between nerve cells.

When mice were handled and forced to swim for a stretch of six minutes - activities known to stress them out without causing harm - a dose of TBG helped chill them out again, giving it an antidepressant quality similar to ketamine.

"Not only does TBG potently promote neuronal growth, it also produces antidepressant-like behavioural responses and reduces alcohol - but not sucrose - consumption in mice," the team wrote in their paper.

While current antidepressants are certainly helpful, figuring out which one works for you involves a horrifying game of trial and error with your brain. This can be a nauseating nightmare that makes you feel far worse before a turn for the better, and can go on for up to eight weeks before it can finally be established if the drug is even working.

After that, ongoing side-effects of antidepressants include insomnia, dizziness, weight gain, and, in some people, the drug's positive effect can wear out over time.

Unlike those medications, psychedelics are thought to change underlying brain circuitry rather than just masking symptoms. A 2018 study found they promote structural and functional neural changes in the prefrontal cortex of rats.

"However, a causal link between psychedelic-induced neuronal growth and behaviour has yet to be established in either humans or rodents," the team cautions in their paper.

A day after rats were treated with TBG, their brain cells were observed to develop more connecting branches (dendritic spines) - but Cameron and team still have to work out if this change in structure is linked to the observed changes in the animals' behaviour.

"With the exception of 18-methoxycoronaridine, which is currently in phase II clinical trials, very few ibogaine analogues have demonstrated this level of safety while also producing therapeutic effects," the team wrote.

There is still much to work out, but these structural changes may be helpful for treating more than one problem.

"We've been focused on treating one psychiatric disease at a time, but we know that these illnesses overlap," Olson said. "It might be possible to treat multiple diseases with the same drug."

With almost 800 million people with mental health disorders worldwide, those of us relying on external help with our brain chemistry would sorely love another, potentially safer option.

This research was published in Nature.