A new technique using diamonds and titanium has the potential to help remove plastic microfibres before they enter the environment, by decomposing them into naturally occurring molecules.

It's a secret the fashion industry would prefer to keep under wraps – most of our synthetic clothes are made of plastic, and they're contributing to a big problem, shedding microplastic fibres into our waste water.

"The release of microplastics into the marine environment is recognised as an important problem related to water pollution. It has been shown that in aquatic environments, these microplastics adsorb toxic substances and can be ingested by aquatic organisms," researchers from the Institut National de la Recherche Scientifique (INRS) in Canada explain in a new paper.

"Afterwards, they accumulate in the food chain and subsequently reach humans."

There are many ways plastic can be shed into the environment, from plastic packaging to car tyres, but until recently one of the largest contributors - microfibres from our clothes - has been mostly overlooked.

When clothes made out of fabrics such as polyester, nylon, and acrylic are washed, tiny plastic microfibres get dislodged from the material and enter the wastewater - and, if they're not removed, our waterways.

The new method for plastic removal - called electrooxidation – doesn't just catch the fibres, but actively deconstructs them.

"Using electrodes, we generate hydroxyl radicals (·OH) to attack microplastics," explains one of the researchers, electrotechnology scientist Patrick Drogui.

"This process is environmentally friendly because it breaks them down into CO2 and water molecules, which are non-toxic to the ecosystem."

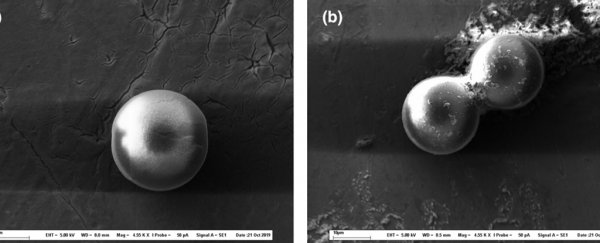

When the researchers did experiments using boron-doped diamond and titanium electrodes on water that was artificially contaminated with 26 µm size polystyrene microbeads, they found that at the six-hour mark, 89 percent of the plastic was degraded.

There are still a few kinks to iron out in this process. Using diamond is unsurprisingly expensive – although the team explains that the components can be reused for a number of years.

The researchers will also need to experiment using actual wastewater to determine if the process is as effective when other contaminants are present. So far, the team has only tested polystyrene plastic.

In the future they hope to integrate something like this in commercial laundries, or potentially even your washing machine, but that's a way off yet.

"When this commercial laundry water arrives at the wastewater treatment plant, it is mixed with large quantities of water, the pollutants are diluted and therefore more difficult to degrade," Drogui said.

"Conversely, by acting at the source, i.e., at the laundry, the concentration of microplastics is higher (per litre of water), thus more accessible for electrolytic degradation."

Currently 80 percent of the world's wastewater isn't treated at all before heading back into the environment, so there's a lot of work yet to do in this area.

It's also important to note that this isn't the only way of removing plastic from our wastewater. Many wastewater treatment plants already use a process that catches 99 percent of particles bigger than 20 micrometres in size, but this still means you have to do something with the plastic once it's been caught – a problem the electrooxidation process solves as well.

Plus, with textile fabrics making up most of the microplastics in the ocean, we're not doing close to enough to remove them.

Obviously one of the easiest ways to stop our clothes shedding plastic is to stop using plastic to produce clothes. This would require huge changes in the ways we produce, consume and regulate clothing manufacturing.

But for all the plastic already within our consumer system, it's good to know there could soon be more ways to remove the microfibres before they have a chance to do potential damage.

The research has been published in Environmental Pollution.