Homo sapiens today look very different from our evolutionary origins, the microbes wriggling about in the primordial mud. But our emergence as a distinct species cannot, based on the current evidence, be conclusively traced to a single location at any single point in time.

In fact, according to a team of scientists, who have conducted a thorough review of our current understanding of human ancestry, there may never even have been such a time. Instead, the earliest known appearances of Homo sapiens traits and behaviours are consistent with a range of evolutionary histories.

We simply don't have a large enough fossil record to definitively rule on a specific time and place in which modern humans emerged.

"Some of our ancestors will have lived in groups or populations that can be identified in the fossil record, whereas very little will be known about others," said anthropologist Chris Stringer of the Natural History Museum in London in the UK.

"Over the next decade, growing recognition of our complex origins should expand the geographic focus of paleoanthropological fieldwork to regions previously considered peripheral to our evolution, such as Central and West Africa, the Indian subcontinent and Southeast Asia."

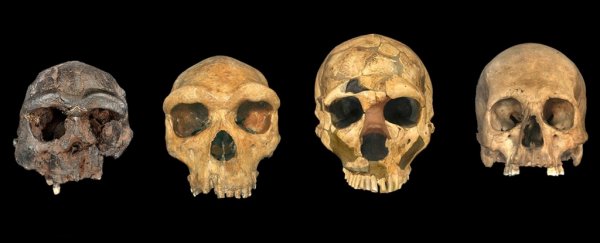

We do have some general ideas about our history. Homo sapiens diverged from archaic ancestors sometime between a million and 300,000 years ago (by which time nine distinct human species populated the planet).

Then, we know that modern human ancestries diversified in Africa between 300,000 and 60,000 years ago.

Finally, between 60,000 and 40,000 years ago, those modern humans migrated out of Africa and across the globe, interbreeding with Neanderthals and Denisovans before those two species ultimately died out.

Based on current evidence, including genomic data and the fossil record, the researchers assert, a more precise location and time in Africa for modern human diversification cannot be identified.

"Contrary to what many believe, neither the genetic or fossil record have so far revealed a defined time and place for the origin of our species," explained geneticist Pontus Skoglund of The Francis Crick Institute in the UK.

"Such a point in time, when the majority of our ancestry was found in a small geographic region and the traits we associate with our species appeared, may not have existed. For now, it would be useful to move away from the idea of a single time and place of origin."

Instead, the researchers stress the importance of trying to separate the emergence of anatomy, physiology, traits and behaviours associated with Homo sapiens from genetic ancestry. This would help separate the question of when human ancestry emerged from when human behaviour emerged.

Conflating the two, they note, risks oversimplifying what was likely a long, continuous and complex process.

"Following from this, major emerging questions concern which mechanisms drove and sustained this human patchwork, with all its diverse ancestral threads, over time and space," said archaeologist Eleanor Scerri of the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History in Germany.

"Understanding the relationship between fractured habitats and shifting human niches will undoubtedly play a key role in unravelling these questions, clarifying which demographic patterns provide a best fit with the genetic and palaeoanthropological record."

The research has been published in Nature.