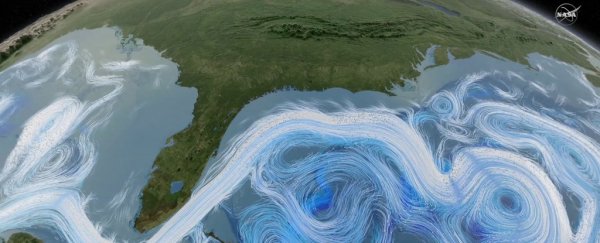

The Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) sea currents are vital in transporting heat from the tropics to the Northern Hemisphere, but new research suggests climate change might knock the AMOC out of action much sooner than we anticipated.

That could have profound, large-scale impacts on the planet in terms of weather patterns, upending agricultural practices, biodiversity, and economic stability across the vast areas of the world that the AMOC influences.

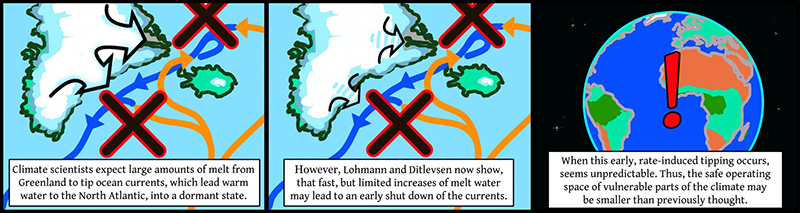

The problem is the rate at which Earth is warming up and melting the ice in the Arctic: according to the researchers' new models, this speed of temperature increase means the risk of hitting the tipping point for the AMOC going dormant is now an urgent concern.

(University of Copenhagen)

(University of Copenhagen)

"It is worrying news," says physicist Johannes Lohmann, from the University of Copenhagen in Denmark. "Because if this is true, it reduces our safe operating space."

Lohmann and his colleague Peter Ditlevsen adapted an existing ocean climate change model to study the consequences of an increased rate of freshwater input into the North Atlantic Ocean, driven by the rapid melting of the Greenland ice sheets.

The model showed that a faster rate of freshwater change could cancel out the AMOC much sooner. In a rate-induced tipping scenario like this, it's the rate at which change is occurring, rather than a specific threshold, that's most important – and once the tipping point is reached, there's no going back.

In other words, the speed at which we're pushing out greenhouse gases and melting ice in Greenland is leaving us with very little room to manoeuvre when it comes to protecting the climate systems that keep global weather patterns in check. The same problem could threaten other climate sub-systems across the world too, the researchers say.

"These tipping points have been shown previously in climate models, where meltwater is very slowly introduced into the ocean," Lohmann told Molly Taft at Gizmodo. "In reality, increases in meltwater from Greenland are accelerating and cannot be considered slow."

The AMOC operates a bit like a giant, looped conveyor belt of seawater, redistributing water and heat around the Northern Hemisphere as the water's temperature, saltiness, and relative weight fluctuates. It's part of the reason that European winters are relatively mild even at higher latitudes.

While it's not clear exactly where the tipping point of the AMOC is, it has been slowing down in recent years, and this new study suggests that the more rapid climate change becomes, the more at risk these currents are. An influx of cold freshwater from Greenland is likely to stop warm water from spreading north, scientists think.

Climate change modelling is incredibly complicated, with so many factors to take into account, and Lohmann and Ditlevsen themselves admit that there's more work to do to figure out the exact details of this rate-induced tipping scenario.

However, they hope it acts as a reminder of just how urgent action on the climate crisis now is: our targets to reduce greenhouse gas emissions need to be as ambitious as possible, whatever the scenario that eventually ends up unfolding in the North Atlantic. We've quite probably got no margin for error left.

"Due to the chaotic dynamics of complex systems there is no well-defined critical rate of parameter change, which severely limits the predictability of the qualitative long-term behaviour," write the researchers in their paper.

"The results show that the safe operating space of elements of the Earth system with respect to future emissions might be smaller than previously thought."

The research has been published in PNAS.