A new study links slight differences in the thickness of gray matter in the brain as an adolescent to an increased risk of psychosis later in life, findings which could one day help doctors detect the condition earlier as well as providing more targeted treatments for it.

The research is notable for its relatively large sample size: MRI scans of 3,169 volunteers with an average age of 21 were analyzed, including 1,792 from people already deemed to be at "clinical high risk for developing psychosis". Of that high-risk group, 253 went on to develop psychosis within two years.

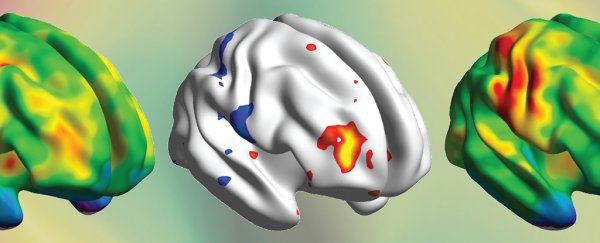

Those at high risk for psychosis generally had lower cortical thickness (the thickness of the brain's gray matter). This was most noticeable in several temporal and frontal brain regions of high-risk youth who later developed psychosis.

Gray matter is the thin outer layer of our brains, lying over most of the brain's structures. It's where our thinking, perceiving, producing, and understanding language and most information processing takes place.

While everyone's brains experience some of this cortical thinning as adulthood arrives, the research also shows that changes can already show up in brain scans of 12-16-year-olds who go on to be diagnosed with psychosis.

"We don't yet know exactly what this means, but adolescence is a critical time in a child's life – it's a time of opportunity to take risks and explore, but also a period of vulnerability," says psychiatrist Maria Jalbrzikowski, from the University of Pittsburgh.

"We could be seeing the result of something that happened even earlier in brain development but only begins to influence behavior during this developmental stage."

While the variations in brain thinning that the researchers found are not statistically different enough to be applied on an individual level, they do point to possible future research areas that are worthy of investigation.

Some cortical thinning has already been reported in some types of psychosis, and these findings may eventually enable scientists to use MRI scans to spot those at greater risk. Currently, around 18-20 percent of those identified as clinically high risk for psychosis go on to develop the condition within two years.

"These results were, in a sense, sobering," says Jalbrzikowski. "On the one hand, our data set includes 600 percent more high-risk youth who developed psychosis than any existing study, allowing us to see statistically significant results in brain structure."

"But the variance between whether or not a high-risk youth develops psychosis is so small that it would be impossible to see a difference at the individual level. More work is needed for our findings to be translated into clinical care."

The term psychosis is used to refer to a number of different conditions, including schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Hallucinations and hearing voices are common; in general, it means someone finding it difficult to tell what is real and what isn't.

Further down the line, the research could help develop a risk score for psychosis and to identify different types more accurately. It's a diagnosis that can have many varying symptoms and experiences, and experts would welcome any help in being able to weigh up and target these variations.

For now, the team behind this latest study wants to look more thoroughly into how brain shape changes over a longer time period – especially covering the years when people are teenagers, which is when the symptoms tend to start to appear.

"Until now, researchers have primarily studied how the brains of people with clinical high risk for psychosis differ at a given point in time," says neuroscientist Dennis Hernaus, from Maastricht University in the Netherlands.

"An important next step is to better understand brain changes over time, which could provide new clues on underlying mechanisms relevant to psychosis."

The research has been published in JAMA Psychiatry.