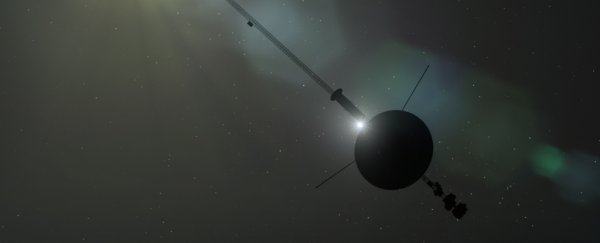

Voyager 1, having spent over 43 years zooming away from Earth since its 1977 launch, is now a very long way away indeed.

Its distance from the Sun is over 150 times the distance between Earth and the Sun. It takes over 21 hours for transmissions traveling at light speed to arrive at Earth. It officially passed the heliopause - the boundary at which pressure from the solar wind is no longer sufficient to push into the wind from interstellar space - in 2012.

Voyager 1 has left the Solar System - and it's finding that the void of space is not quite so void-like, after all.

In the latest analysis of data from the intrepid probe, from a distance of nearly 23 billion kilometers (over 14 billion miles), astronomers have discovered, from 2017 onwards, a constant hum from plasma waves in the interstellar medium, the diffuse gas that lurks between the stars.

"It's very faint and monotone, because it is in a narrow frequency bandwidth," said astronomer Stella Koch Ocker of Cornell University. "We're detecting the faint, persistent hum of interstellar gas."

Obviously we know that interstellar space isn't completely empty, but since stars are so bright, the vastly fainter wispy material that hangs out between them is really hard to see and measure. Usually, we have to rely on the way light changes when it travels through interstellar material to know it's there, and to quantify it.

The Voyager probes are the first human-made objects to enter interstellar space, and therefore represent a unique opportunity to sample the interstellar medium directly.

Even so far from the Sun, though, and even beyond the reach of the solar wind, it's not exactly easy. The Sun is still a bright and a noisy beast, letting out solar eruptions that can drown out the ambient conditions.

"The interstellar medium is like a quiet or gentle rain," said astronomer James Cordes of Cornell University. "In the case of a solar outburst, it's like detecting a lightning burst in a thunderstorm and then it's back to a gentle rain."

That gentle rain, according to the team, suggests that there could be more low-level activity in the interstellar medium than scientists had thought. What that activity is caused by is not entirely clear; it could be thermally excited plasma oscillations, or quasi-thermal noise generated by the movements of electrons in plasma, producing a local electric field.

Whatever is causing it, the discovery has several implications. The hum can be used to map the plasma density as both Voyager probes move deeper into interstellar space (Voyager 2 crossed the heliopause in 2018).

It can also be used to better understand the interaction between the interstellar medium and the solar wind. We know there's an increase in electron density just on the other side of the heliopause - both Voyager probes detected it when they traveled on through. Knowing the density of the interstellar medium more accurately can help us figure out why.

The discovery and the persistence of the emission also suggest that Voyager will continue to be able to detect it, providing us with ongoing readings that will help us understand turbulence and the large-scale structure of the interstellar medium.

"We've never had a chance to evaluate it. Now we know we don't need a fortuitous event related to the Sun to measure interstellar plasma," said astronomer Shami Chatterjee of Cornell University.

"Regardless of what the Sun is doing, Voyager is sending back detail. The craft is saying, 'Here's the density I'm swimming through right now. And here it is now. And here it is now. And here it is now.' Voyager is quite distant and will be doing this continuously."

Not forever, though. The radioisotope thermoelectric generator powering the probe's instruments degrades a little bit more every year. By around 2025, it may no longer be able to keep them running.

Which is why it is so important to glean as much data as we can, while there's still the opportunity.

The research has been published in Nature Astronomy.