Although we might think of ourselves as far removed from blobby green algae, we're not really that different.

An algae explosion a few hundred million years ago is thought to have been what allowed all human and animal life to evolve, and all told there's only about one and a half billion years between us in terms of evolution.

Plus, according to a Japanese team of researchers, algae could actually help us to understand how different sex systems - like male and female - evolved in the first place.

Researchers from the University of Tokyo and a number of other Japanese universities have discovered that a type of green algae called Pleodorina starrii has three distinct sexes – 'male', 'female', and a third sex that the team have called 'bisexual'. This is the first time any species of algae has been discovered with three sexes.

"It seems very uncommon to find a species with three sexes, but in natural conditions, I think it may not be so rare," said one of the researchers, University of Tokyo biologist Hisayoshi Nozaki.

Algae isn't a very specific scientific classification. It's an informal term for a huge collection of different eukaryotic creatures that use photosynthesis to get energy. They're not plants, as they lack many plant features; they're not bacteria (despite cyanobacteria sometimes being called blue-green algae); and they're not fungi.

Everything from many-celled giant kelp species, all the way down to cute single-celled dinoflagellates can be classed as algae.

Because algae are such a big, diverse group, there's lots of variation in the way that they get it on, but generally algae are able to reproduce asexually (by cloning themselves) or sexually (with a partner), depending on the life cycle stage they're in. This can be either haploid (with a single set of chromosomes), or diploid (with two sets).

There's also hermaphroditic algae that can change depending on the gene expression of the organism. Having three sexes, including hermaphrodites, is called 'trioecy'.

But the volvocine green algae P. starrii is different from this again. The bisexual form of this haploid algae has both male and female reproductive cells. The team describe it as a "new haploid mating system" completely unique to algae.

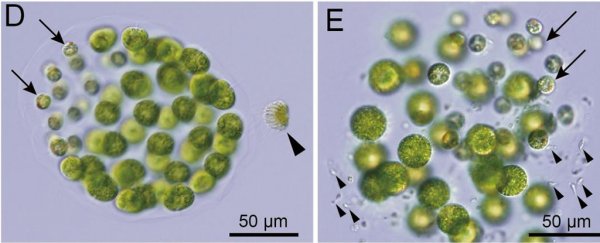

P. starrii form either 32 or 64 same-sex celled vegetative colonies and have small mobile (male) and large immobile (female) sex cells similar to humans. The male sex cells are sent out in the world in sperm packets to find a female colony to attach to.

Bisexual P. starrii have both, can form either male or female colonies, and therefore can mate with either a male, a female, or another bisexual.

(Kohei Takahashi)

(Kohei Takahashi)

Above: Sexually induced male colony of algae (left). Female colony with male sperm packet (center). Female colony with dissociated male gametes (right).

The researchers are particularly excited because other closely related algae have different sex systems, meaning the discovery might be able to tell us more about how these sexual changes evolve.

"Mixed mating systems such as trioecy may represent intermediate states of evolutionary transitions between dioecious (with male and female) and monoecious (with only hermaphrodites) mating systems in diploid organisms," the team write in their new paper.

"However, haploid mating systems with three sex phenotypes within a single biological species have not been previously reported."

For 30 years, Nozaki had been collecting algae samples from the Sagami River outside of Tokyo. Samples that were taken from lakes along that river in 2007 and 2013 were used by the team for the new finding.

The team separated the algal colonies and induced them to reproduce sexually by depriving them of nutrients, discovering that the bisexual algae had a 'bisexual factor' gene that was separate to previously discovered male and female specific genes.

The bisexual cells had the male gene as well, but can produce either male or female offspring.

"Co-existence of three sex phenotypes in a single biological species may not be an unusual phenomenon in wild populations," the researchers conclude.

"The continued field-collection studies may reveal further existence of three sex phenotypes in other volvocine species."

The research has been published in Evolution.