A rigorous international inquiry into the genetics of endometriosis has revealed a potential new drug target for what remains a very common and incurable disease.

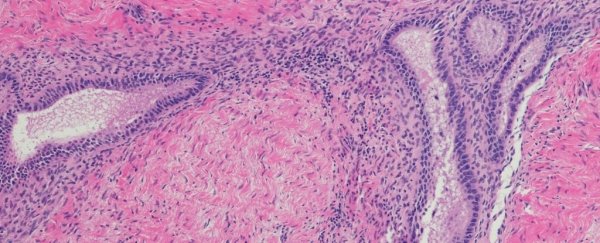

Endometriosis occurs when tissue similar to the uterus grows outside of the womb, oftentimes leading to chronic pain, although not in every case.

After decades of neglect from researchers and doctors alike, the reality is we still know very little about this inflammatory condition, which predominantly impacts women of reproductive age.

Treatments currently include surgery to remove the endometrial lesions and hormones to control their growth, but both have imperfect results and come with their own risks and side effects.

Alternative treatments are desperately needed, and because endometriosis is commonly inherited, drug researchers are turning to genetics for clues.

The first parallel investigation of both humans and rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) has now revealed a possible focus for future drug treatment; it's one that isn't based on hormones, which can come with a whole lot of side effects.

It began with a 2015 study at Oxford University on 32 families containing three or more endometriosis patients. Here, researchers found a genetic link between stage III/IV endometriosis and a region of the human chromosome called 7p13-15.

That was a good starting point, but this region alone holds hundreds of genes. In the end, it took several more years of research at the Baylor College of Medicine in Texas to locate the specific gene researchers were looking for.

When researchers sequenced the DNA of 849 macaques – 135 of which had developed spontaneous endometriosis – they noticed a variation in the gene NPSR1, which is located on the chromosome 7p13-15 and seems to increase the risk of suffering from late-stage endometriosis.

Back at Oxford, researchers sequenced the DNA of more than 11,000 women, including 3,000 women with endometriosis, to see if they could find a similar genetic variation in humans. Their results ultimately found stage III/IV endometriosis is associated with the same specific variant in the NPSR1 gene as found in macaques.

In the past, variations of the NPSR1 gene have been linked to several other inflammatory conditions, such as asthma, allergies, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), rheumatoid arthritis, and recurrent abdominal pain – some of which are known to co-occur with endometriosis.

But the variation, in this case, was slightly different from what has been found before with, say, IBD.

"This is one of the first examples of DNA sequencing in nonhuman primates to validate results in human studies and the first to make a significant impact on understanding the genetics of common, complex metabolic diseases," says Jeffrey Rogers from the Baylor College of Medicine.

"The primate research really helped to provide confidence at each step of the genetic analysis in humans and gave us motivation to carry on chasing these particular genes."

In recent years, a growing number of researchers have come to suspect that endometriosis is not just one disease, but is in fact made up of several different subtypes.

There's even been some preliminary evidence that the various stages of endometriosis are genetically distinct, but at the moment, there are no drugs available that target these specific variations.

The late stages of endometriosis are usually defined by a higher number of lesions with deeper infiltration, and yet that doesn't always correlate with greater pain or worsening symptoms.

The way that endometriosis presents can vary quite a lot from patient to patient, and no one really knows why or how best to treat the various symptoms.

Even in the current research, not every endometriosis patient studied at Oxford University had an NPSR1 variant, which means that if a drug can be developed to target this subtype, it probably won't work for everyone.

Still, that doesn't mean it's not worth pursuing. When researchers inhibited the NPSR1 gene's expression in mice, which had little pieces of uterine lining implanted into their abdomens to simulate endometriosis, the animals showed signs of reduced inflammation and abdominal pain.

"We need to do further research on the mechanism of action and the role of the genetic variants in modulation of the gene's effects in specific tissues," says genetic epidemiologist Krina T. Zondervan from Oxford University.

"However, we have a promising new non-hormonal target for further investigation and development that appears to address directly the inflammatory and pain components of the disease."

Just like in any emerging field, this study has limitations. A relatively small number of patients were initially studied at Oxford University and the functional effects of the NPSR1 gene changes weren't able to be investigated.

While mice seemed to have their pain decreased somewhat when this genetic variant was turned off, Stacy McAllister, an endometriosis researcher at Emory University who was not involved in the study, told Science Magazine she'd like to know if the results can be extended from acute pain relief to chronic pain relief, which is the main complaint among patients with endometriosis.

What's more, because mice do not menstruate, their models of this suspected inflammatory disease can only tell us so much. The authors of the current study admit their results do not feature the 'full disease spectrum' or the 'pathological nuances' we seen in humans.

As such, they hope to conduct further research on NPSR1 variants and their functional effects among macaques. If researchers can target the gene in monkeys in a similar way to mice, we can begin to test out certain drug treatments, working our way up to clinical trials in humans.

That reality is still a ways off, but given the debilitating toll endometriosis can take on the lives and livelihoods of women around the world, it's vital we find a better way to treat this disease.

The study was published in Science Translational Medicine.