Motes of weathered plastic increasingly dust every corner of our planet, permeating our food, our air, and our water. From the moment we're born – if not long before – we're exposed to its effects, and we don't fully know what that's doing to our health and wellbeing.

A recent investigation by a team of researchers in Nanjing, China, has uncovered worrying signs that elevated levels of microplastics could be inflaming our digestive systems.

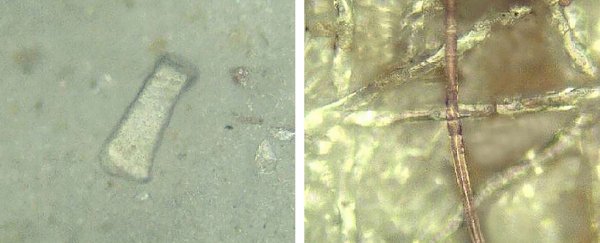

Feces collected from 52 individuals diagnosed with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) were found to contain around 1.5 times the number of plastic particles smaller than 5 millimeters (about 0.2 inches) than similar samples from volunteers without any chronic illnesses.

The vast majority of plastic particles were smaller than 300 micrometers, with a few detectable pieces coming in below a minuscule 5 micrometers across. The researchers noticed those with IBD also tended to have a greater proportion of smaller flakes of microplastic.

What's more, the greater the plastic load, the more severe the individual's IBD symptoms.

A survey revealed nothing unusual about the origins of the plastic, suggesting it was the kinds of particles we all might ingest by drinking from PET bottles or eating out of single-use disposable containers.

As an observational study, the research doesn't establish cause and effect. Nobody can claim the difference in microplastic load is solely, or even partially responsible for the symptoms of diarrhea, rectal bleeding, and abdominal cramping associated with the illness.

It's even possible having IBD might make it harder to clear the build-up of plastic detritus that accumulates in our diets.

But the mere possibility of a connection is concerning enough to warrant further investigation, especially given the shocking rate at which plastic waste is spreading virtually unabated.

Seven million people globally were diagnosed with IBD in 2017, a condition distinguished by regular bouts of discomfort and changes in bowel motion produced by a hair-trigger system overreacting to otherwise benign materials in the gut.

The illness usually falls into one of two main diagnoses: Crohn's disease, which is typically characterized by an inflamed lining throughout the deeper layers of the digestive tract, and ulcerative colitis, which is marked by ulcers in the large intestine's lining.

In either case, the ultimate source of the errant immune response isn't yet fully understood, though suspicions lie with the complex way our guts negotiate diplomatic relations with our microflora, particularly during an infection.

Whether plastic particles might somehow involve themselves with a link in this chain has never been fully made clear, though animal studies have previously pointed to gut inflammation as a possible side effect of microplastic exposure.

Circumstantially, microplastics have also been shown to stir up trouble by generating reactive oxygen species that are known to play a role in inflammation.

With that in mind, it's not at all surprising to imagine an increase in gut exposure to microplastic particles might play a similar role to certain microbes in sensitizing the lining to an exaggerated immune reaction.

Further studies will be needed before we can claim with any confidence that our dietary supplement of plastic dust is putting us at increased risk of any health problems. There are still too many unknowns.

But that doesn't mean we shouldn't be taking action. Evidence that the rising tide of plastic waste is affecting everything from the climate to the distribution of species to the health of marine life is mounting.

That our health might be just one more consequence is just more reason to wean ourselves off our dependence on this pervasive pollutant.

This research was published in Environmental Science & Technology.