The human body might not cope with nearly as much heat and humidity as theory predicts.

One of the first studies to directly assess humid heat stress among young people has found that when humidity is at an absolute max, the upper limit of human adaptability is just 31°C (87 °F).

That's four degrees less than theoretical estimates, and for older people, the threshold is probably even lower.

Because humans cool themselves through evaporative cooling (as in, the sweat on your skin helps to cool you down), it's important to understand 'wet-bulb temperature', which incorporates both heat and humidity – the more humidity in the air relative to heat, the harder it is for evaporation to work.

Compared to hot and dry climates, the human body cannot withstand hot and humid climates nearly as well. That's because at 100 percent humidity, our sweat cannot dissipate as easily to cool our bodies down.

In an absolutely dry environment, the human threshold for survival is probably around 50 °C. But for a completely humid environment, the new results suggest temperatures need only reach 31 °C before our bodies go into heat stroke.

With prolonged exposure to such conditions, death is inevitable.

"If we know what those upper temperature and humidity limits are, we can better prepare people – especially those who are more vulnerable – ahead of a heat wave," says physiologist Larry Kenney from Pennsylvania State University.

"That could mean prioritizing the sickest people who need care, setting up alerts to go out to a community when a heatwave is coming, or developing a chart that provides guidance for different temperature and humidity ranges."

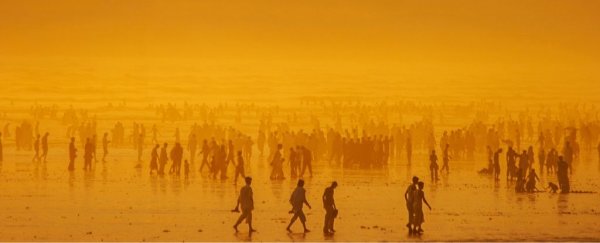

As climate change drives excessive global warming and water evaporation, increasing the heat and moisture of our atmosphere, the threat of exceeding wet-bulb temperature thresholds becomes ever more likely. Especially in the tropics.

Climate scientists suspect that by the end of the century, Pakistan, India, and parts of Southeast Asia, the Persian Gulf and Central America will experience max humidity levels at temperatures over 35 °C much more often.

But this cut-off is based mostly on theory and physiological models of how much heat and humidity the human body can stand. Real-word data have so far been lacking.

To figure out the actual wet-bulb temperature at which humans hit the risk of heat stroke and potential death, researchers recruited 24 young and healthy adults between 18 and 34 years of age.

The team started with a young and fit cohort of humans as they can give us a 'best case' baseline. Older people, pregnant people and other vulnerable populations are generally not able to tolerate heat and humidity as well.

Before entering a chamber with adjustable temperature and humidity levels, participants swallowed a tiny recording device to measure their core body temperatures and relay that information to the researchers via radio.

Then, participants were asked to slowly cycle on a stationary exercise bike, as the temperature and humidity of the chamber was gradually increased.

When the participant's body was no longer able to maintain a core temperature, the experiment was stopped.

On average, in these conditions critical wet-bulb temperatures ranged from 30°C to 31°C, although they could be a little higher if the person is at complete rest and not moving a muscle.

Researchers are now hoping to replicate these studies among older participants, but the fact that this threshold is so low compared to previous estimates, even for young and fit participants, is worrisome.

In 2020, several cities in Pakistan recorded wet-bulb temperatures over 35°C. Since 1979, the frequency of wet-bulb temperatures over 31°C has more than doubled.

While the new experiments suggest young people are vulnerable to such extremes, statistics show older people are still more likely to die with prolonged exposure.

"Our results suggest that in humid parts of the world, we should start to get concerned – even about young, healthy people – when it's above 31 degrees wet-bulb temperature," says Kenney.

"The climate is changing, so there are going to be more – and more severe – heat waves. The population is also changing, so there are going to be more older adults. And so it's really important to study the confluence of those two shifts."

The study was published in the Journal of Applied Physiology.