At the distant end of the Solar System, far from the Sun's warmth and light, a truly unique world drifts in the alien darkness.

Pluto, new research has found, has a landscape sculpted by ice volcanoes, of a type and scale seen nowhere else in the Solar System. To the south-west of the Sputnik Planitia, so much slush has erupted from below the surface of Pluto that mountains of ice stand up to 7 kilometers (4.3 miles) high.

"One of the regions with very few impact craters is dominated by enormous rises with hummocky flanks. Similar features do not exist anywhere else in the imaged Solar System," writes a team of researchers led by planetary scientist Kelsi Singer of the Southwest Research Institute.

"The existence of these massive features suggests Pluto's interior structure and evolution allows for either enhanced retention of heat or more heat overall than was anticipated before New Horizons."

As the name indicates, rather than hot molten lava, ice volcanoes erupt with slushy water slurries of volatile compounds such as ammonia and methane. Once they emerge into frigid atmospheric conditions above ground, they freeze and build up surface monuments, much like lava can create volcanic mountains and calderas, just… well, colder.

The first hint of ice volcanoes, known as cryovolcanism, was detected on Pluto in 2015, when the New Horizons probe made its epic flyby of our Solar System's erstwhile ninth planet.

Never before had scientists had access to such a wealth of data on the Kuiper Belt's largest known inhabitant; and, not far from the heart-shaped flatland of the Sputnik Planitia, some features stood out as truly interesting.

Of these, Wright Mons and Piccard Mons were tentatively identified as ice volcanoes, large mounds with what appeared to be deep holes in their centers, very similar to volcanic features elsewhere in the Solar System.

Later analysis by Singer and colleagues revealed that the elevations of the topography might appear more pronounced than they are, due to the oblique lighting at the terminator (the line that separates night and day), confusing the issue slightly.

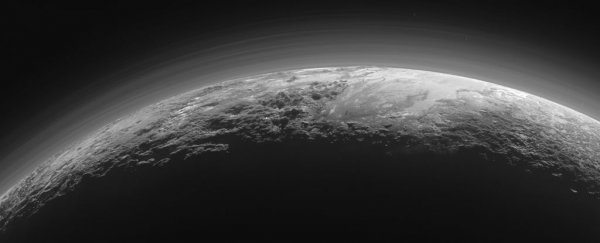

Perspective view of cryovolcanic terrain on Pluto. (NASA/JHU APL/SwRI/Isaac Herrera/Kelsi Singer)

Perspective view of cryovolcanic terrain on Pluto. (NASA/JHU APL/SwRI/Isaac Herrera/Kelsi Singer)

Now, Singer and her team have conducted an in-depth analysis and found the terrain is still likely sculpted by cryovolcanism. The reason it might look different from other such terrains in the Solar System is that the processes and environment are different; "unique to Pluto", they wrote.

Moreover, it had to have taken place fairly recently in the dwarf planet's history. That's because there's only one crater on the side of Wright Mons, suggesting that it hasn't had enough time to become pocked and scarred by multiple impacts.

Features suggestive of ice volcanoes have been spotted on multiple worlds throughout the Solar System, including dwarf planet Ceres, Saturn's moon Titan, Jupiter's moon Europa, and even Pluto's moon Charon. But cryovolcanism can be hard to positively identify, because there are no current processes on Earth of the same nature with which we can compare it.

Cryovolcanic terrain on Pluto, with possible past activity marked in blue. ((NASA/JHU APL/SwRI/Isaac Herrera/Kelsi Singer)

Cryovolcanic terrain on Pluto, with possible past activity marked in blue. ((NASA/JHU APL/SwRI/Isaac Herrera/Kelsi Singer)

In the cryovolcanic landscape at the edge of the Sputnik Planitia, many such mounds have proliferated, Singer and team found. The creation of such a terrain would require multiple eruption sites, and a large volume of erupted material – around 10,000 cubic kilometers, or 4 billion Olympic swimming pools' worth. The volume of Wright Mons alone is comparable to the Mauna Loa caldera in Hawaii.

It's unclear exactly what processes in the depths of Pluto might have produced such a scale of cryovolcanism. It's possible there is a deep network of fractures below the terrain, one that has since been covered up by the oozing and hardening cryomagma.

The new discovery suggests that, although it's frozen, Pluto may be very far from dead and inert. In fact, the tiny, distant dwarf planet may have a lot to teach us about cryovolcanism.

"The range of cryovolcanic features found across the Solar System is diverse. With the different conditions and surface materials present at Pluto, it is quite possible that any material movement onto the surface may not resemble that of other bodies," the team wrote.

"The extrusion of icy material onto the surface of a body with extremely low temperatures, low atmospheric pressure, low gravity, and the abundance of the volatile ices found on Pluto's surface make it unique among the visited places in the Solar System."

The research has been published in Nature Communications.