The term 'microplastic' was coined only 18 years ago, and already they seem to be just about everywhere.

Each year, the average human consumes an estimated 74,000 particles of plastic with unknown health effects. In March of this year, scientists announced they'd found microplastics flowing through our very veins.

Turns out, they're also circulating at low levels deep in our lungs.

The most robust study of its kind has discovered 39 microplastic particles (each at least three micrometers in size) in 11 out of 13 lung tissue samples from living humans.

Previous studies on cadavers and lung cancer samples have uncovered tiny fibers and flakes of plastics before, but none analyzed the makeup of the synthetic polymers.

Of the types of microplastic detected in this latest study, a dozen polymer types showed up the most. These included polyethylene, which is found in plastic bags and packaging, resin from paints, roads, and tires, and nylon from clothing.

While these microplastics were only found in small amounts, they were present throughout the lungs, and the lower the lung tissue, the more contamination there generally was.

This deep in the lungs, the plastic particles were unexpectedly large.

"This is surprising as the airways are smaller in the lower parts of the lungs, and we would have expected particles of these sizes to be filtered out or trapped before getting this deep into the lungs," explains respiratory specialist Laura Sadofsky from Hull York Medical School in the UK.

(Jenner et al., Science of the Total Environment, 2022)

(Jenner et al., Science of the Total Environment, 2022)

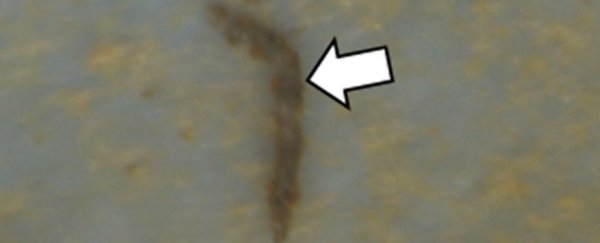

Above: Images of microplastics found in human lung tissue.

For decades it's been thought that only particles with a physical diameter below 3 μm can enter the alveolar region of the lung. Today, in the scientific literature, the alveolar duct is said to have a diameter of about 540 μm and a length of 1,410 μm.

But the current study found particles ranging up to 2,475 μm in length and up to 88 μm in width, which they note is "too large to be present, yet present nonetheless".

The findings suggest that inhalation is a regular route of microplastic exposure for humans, and that we may be breathing larger particles than experts assumed.

Apart from that, we know very little. It's unclear, for instance, what low levels of microplastics in our lungs are actually doing to human health, if anything at all.

"This data provides an important advance in the field of air pollution, microplastics and human health," says Sadofsky.

"The characterization of types and levels of microplastics we have found can now inform realistic conditions for laboratory exposure experiments with the aim of determining health impacts."

The study was published in Science of the Total Environment.