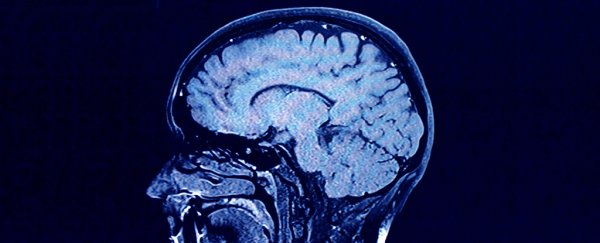

A devastating and potentially deadly eating disorder, anorexia nervosa exerts its toll on the body. However, a new study also highlights the impact a lack of sufficient nutrition can have on the brain, by seriously reducing critical measures of brain structure and health.

Based on a total of 1,648 female brain scans (685 with anorexia nervosa) collected from 22 different locations, researchers found decreases in cortical thickness, subcortical volumes and cortical surface area in people with anorexia. Essentially, the brain sort-of shrinks down.

In terms of sample size, it's the largest study carried out to date to look at the relationship between the eating disorder and gray matter – and it shows how important it is to treat the condition as early in its development as possible.

"For this study, we worked intensively over several years with research teams across the world," says psychologist Esther Walton, from the University of Bath in the UK.

"Being able to combine thousands of brain scans from people with anorexia allowed us to study the brain changes that might characterize this disorder in much greater detail."

The reductions in the size and shape of the brain shown here are two to four times larger than reductions caused by other psychological conditions such as depression, ADHD, and OCD, the researchers say.

What's causing these reductions isn't covered by this study, but the team behind it suggests that reductions in body mass index (BMI) and the amount of nutrients available are likely to have something to do with it.

However, there are signs of hope in the research as well: the brain scans showed that anorexia treatments, which typically involve cognitive behavioral therapy, can possibly reverse some of these changes in the brain.

"We found that the large reductions in brain structure, which we observed in patients, were less noticeable in patients already on the path to recovery," says Walton.

"This is a good sign, because it indicates that these changes might not be permanent. With the right treatment, the brain might be able to bounce back."

While scientists aren't sure about what causes anorexia to take hold, we know much more about its effects. Millions of people worldwide are affected by it, and it's one of the leading causes of death related to mental health problems.

As more data come in from future studies, scientists will be able to better understand exactly what is causing this reduction in brain volume in people with anorexia, and some of the neurological mechanisms behind it.

For now, it's clear that the earlier treatment is sought and given, the better. The same techniques used here could also be used to measure the effectiveness of treatments on the damage being done to the brain.

"Effects of treatments and interventions can now be evaluated, using these new brain maps as a reference," says neurologist Paul Thompson from the University of Southern California.

"This really is a wake-up call, showing the need for early interventions for people with eating disorders."

The research has been published in Biological Psychiatry.