Most families have a skeleton in the closet. One where Cousin Jo or Great Uncle Bob turns out not to be a genetic relative after all.

Now we all have one such mistaken relative. Your dog, gold fish, and canary included.

Five years ago, an analysis of tiny 540-million-year-old fossils from China concluded the specimens were the oldest examples of a branch of the animal kingdom known as deuterostomes, a classification that includes things like starfish, crinoids, and – surprisingly – all vertebrates.

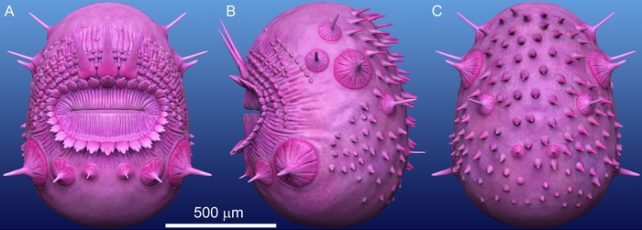

Barely bigger than a grain of rice, this ancient creature (named Saccorhytus coronarius) couldn't look less like a backboned animal if it tried. It didn't even have a bum to poop from. It was just a big, bumpy mouth on a pouch.

Surrounding that pretty little crowned gob, however, was a series of folds and holes that resembled primitive versions of features that might eventually evolve into gills and throats. Or so it was thought.

Called pharyngeal openings, those wrinkles and holes are fairly definitive bits of anatomy in the evolution of deuterostomes, potentially making Saccorhytus an early representative.

Now a closer look at a number of newly uncovered specimens using scanning electron microscopy and X-rays generated by a particle accelerator suggests this strange creature might not belong in the vertebrate family photo album after all.

The latest descriptions give us a better idea of what the animal would have looked like. Its millimeter-long (about 0.04 inch) body was slightly elongated, almost tear-drop-shaped with a tough, dual-layered outer shell.

Surrounding its mouth were some radial folds and a ring of bumps, with more raised nodules poking from its sides.

What previous examinations took for pores in a single layer of delicate skin appear to instead be gaps in a harder, multi-layered 'shell' that allowed spines from a decayed lower layer to poke through.

"We believe these would have helped Saccorhytus capture and process its prey," says Huaqiao Zhang, a paleontologist from the Chinese Academy of Sciences.

These differences in anatomy play a crucial part in determining where Saccorhytus sits in taxonomy. No longer endowed with folds and holes that might eventually morph into gills and throats, the fossils exhibit few features that put it on the fringes of our section of the animal kingdom.

Researchers were left instead with a hard-shelled, spiky, bum-faced critter that looks all the world like a nightmare version of Pac-Man pitched by filmmaker Guillermo del Toro.

"We considered lots of alternative groups that Saccorhytus might be related to, including the corals, anemones, and jellyfish which also have a mouth but no anus," says University of Bristol paleontologist Philip Donoghue, who co-led the study.

That whole 'no bum' thing was eventually considered a red herring.

Their conclusion now puts the animal firmly in the ecdysozoan part of the animal kingdom, making it an ancestor of invertebrates. Ancestors of ecdysozoa would have evolved an anus by then, implying Saccorhytus would have ditched its bum for some reason.

To test their hypothesis that Saccorhytus and its ilk were destined to give rise to bugs and not bears, the researchers ran a series of statistical tests relating the fossil's characteristics to diverse features from all across the animal kingdom.

"To resolve the problem our computational analysis compared the anatomy of Saccorhytus with all other living groups of animals, concluding a relationship with the arthropods and their kin, the group to which insects, crabs, and roundworms belong," says Donoghue.

Sure enough, this weird tiny creature has more in common with the ancestors of ants than us.

It might seem like a radical leap from one category to another, but taxonomy can rely on translating the smallest details into recognizable features, something that demands perfectly preserved specimens at the best of times.

Turning squished, half-decayed exo-skeletons from half a billion-years ago into something that belongs in any kind of family album is truly a remarkable feat.

"We still don't know the precise position of Saccorhytus within the tree of life but it may reflect the ancestral condition from which all members of this diverse group evolved," says Virgina Tech paleobiologist Shuhai Xiao, who also co-authored the study.

No doubt Cousin Jo will be gossiping about this one at family reunions for years.

This research was published in Nature.