It's been easy to feel disconnected over the past two and a half years, despite all the hours spent doing Zoom trivia and online gaming with friends.

But it turns out that, even when we're physically alone, our brains may be able to sync up with the minds of others we're playing with better than expected.

A new study has shown that people playing a cooperative game together online can achieve brainwave synchronization, even when they're in total isolation.

This type of synchronization is usually associated with social interaction, and is important to a healthy society because it's linked to better empathy and cooperation.

But this new research suggests it doesn't only happen when we're face to face.

"We were able to show that inter-brain phase synchronization can occur without the presence of the other person," says one of the team, cognitive researcher Valtteri Wikström from the University of Helsinki in Finland.

"This opens up a possibility to investigate the role of this social brain mechanism in online interaction."

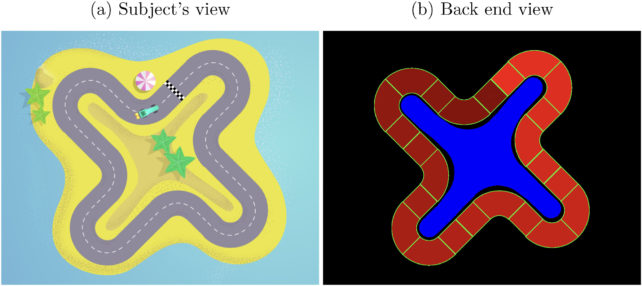

In the study, 42 Finnish students were put into pairs and asked to play a specially designed game where they worked together to control a racing car around four different tracks.

One controlled the speed and one controlled the direction, and the participants would switch roles after completing a run, playing each track twice.

The two participants were split up into two separate soundproof rooms, so they had no physical interaction.

They also weren't communicating with each other outside of the actions performed in the game, so there was no headset involved.

At the same time, both students were hooked up to EEG (electroencephalography) scanners, so the researchers could monitor their real-time brain activity through electrical signals and see how well it matched each other's.

What the team found was that the players actually achieved brainwave synchronization across alpha, beta, and gamma waves.

To help ensure the effect was real, the team also created 'false pairs' from the data – participants with similar times for getting around the track, but who hadn't actually played together.

This meant the researchers could also show that the brain synchronization wasn't simply happening across everyone who performed in a similar way, and was unique to those who'd played together.

Brain connection also appeared to be linked to success in the game.

The more synced up the participants' gamma rays were, the better short-term performance in the game. And the higher their alpha synchrony, the better they did overall.

Over the course of a gaming session, brains became less synced, but then they become even more synchronized during the second session compared to the first.

We're still very fresh into our understanding of how brains interact when they connect with other minds online, so we have a lot to learn about what's going on here.

But we already know that gaming can help our brain practice some vital decision-making skills. And it's promising to now know there may be opportunities in the future to use gaming to make us all feel a little more in sync, and perhaps also more empathetic to each other.

"This study shows that inter-brain synchronization happens also during cooperative online gaming, and that it can be reliably measured," says Wikström.

"Developing aspects in games that lead to increased synchronization and empathy can have a positive impact even outside of gaming."

The next step is to find a way to measure the quality of these online interactions, and also figure out which aspects of working together in an online game are best promoting the type of connectedness we get from social interaction.

This is important, particularly in a world where more and more of our learning and connection is inevitably happening online – and yet we still don't fully understand the implications of that for social brain development.

"If we can build interactive digital experiences which activate fundamental mechanisms of empathy, it can lead to better social relationships, well-being, and productivity online," says cognitive neuroscientist Katri Sarrikivi, who managed the research project.

The research has been published in Neuropsychologia.