You'll no doubt be familiar with the dry, dusty appearance of Mars as it looks today – but scientists have found evidence of a vast ocean existing on the surface of the red planet around 3.5 billion years ago, likely covering hundreds of thousands of square kilometers.

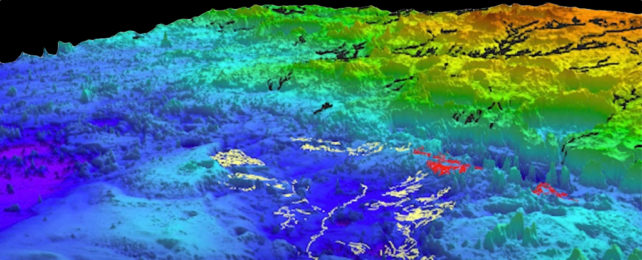

That evidence comes in the form of distinctive shoreline topography, identified through numerous satellite images of the Martian surface. When these images are snapped at slightly different angles, a relief map can be constructed.

Researchers have been able to chart out more than 6,500 kilometers (4,039 miles) of fluvial ridges, apparently carved out by rivers, demonstrating that they are most likely eroded river deltas or submarine-channel belts (channels carved out on the seafloor).

"The big, novel thing that we did in this paper was think about Mars in terms of its stratigraphy and its sedimentary record," says geoscientist Benjamin Cardenas from Pennsylvania State University.

"On Earth, we chart the history of waterways by looking at sediment that is deposited over time. We call that stratigraphy, the idea that water transports sediment and you can measure the changes on Earth by understanding the way that sediment piles up. That's what we've done here – but it's Mars."

Using data from the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter collected in 2007, the team applied an analysis of ridge thicknesses, angles and locations to understand the area of study: the topographical depression known as the Aeolis Dorsa region on Mars.

It seems probable that a significant amount of change was happening on this part of the planet all those years ago, Cardenas explains. This is shown by the evidence of substantial sea level increases and the rapid movement of rocks by rivers and currents. Today, Aeolis Dorsa contains the most concentrated collection of fluvial ridges on Mars.

All this ties into the search for life on Mars. One of the most fundamental questions scientists are looking at in regards to the red planet is whether it has ever had conditions that are hospitable enough to be able to support life.

"What immediately comes to mind as one the most significant points here is that the existence of an ocean of this size means a higher potential for life," says Cardenas.

"It also tells us about the ancient climate and its evolution. Based on these findings, we know there had to have been a period when it was warm enough and the atmosphere was thick enough to support this much liquid water at one time."

The researchers aren't stopping with the Aeolis Dorsa region.

In a separate study published in Nature Geoscience, some of the same researchers, including Cardenas, applied an acoustic imaging technique used to map ancient seafloors in the Gulf of Mexico to a model of how water may have eroded the surface of Mars.

There are huge areas of what might be fluvial ridges all across Mars, and the simulations run by the team are remarkably similar to the shape of the landscape on the red planet – suggesting that there was extensive water coverage at one time.

We're seeing more and more signs that water was once abundant on Mars, and work continues to figure out what it might have led to and where that water is now – though looking back through billions of years of time isn't easy.

"If there were tides on ancient Mars, they would have been here, gently bringing in and out water," says Cardenas. "This is exactly the type of place where ancient Martian life could have evolved."

The research has been published in Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets and Nature Geoscience.